Participation of Indigenous Peoples at the UN is crucial for advancing their rights

24 September 2024

The advancement of Indigenous Peoples’ rights has come a long way, especially concerning the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination. However, experts note that barriers to true equality in participation remain.

“We have to be vigilant, and we have to be able to have a voice at the highest levels of the UN to make sure our rights are protected, and that Indigenous Peoples can survive long into the future,” said Kenneth Atsenhaienton Deer, award-winning journalist, educator and an internationally known Indigenous rights activist.

Deer is a member of the Bear Clan of the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka or Mohawk Nation, in the Kahnawake territory. The Mohawk Nation is one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy or Haudenosaunee, Deer’s Haudenosaunee name, Atsenhaienton, means “the fire still burns”.

Deer and other Indigenous advocates will attend the interactive dialogue with the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) and the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples at the 57th session of the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

One of the main challenges to ensuring the full participation of Indigenous Peoples in the UN has to do with who is allowed to participate. Current UN rules state that mostly Member States and NGOs with consultative status can interact with the UN. Interactions include submitting questions, attending sessions, and even holding side events.

“And so, it's very difficult for Indigenous Peoples to manoeuvre there because we are not NGOs,” Deer said.

Kenneth Atsenhaienton Deer at the UN in New York in 2014. © Kenneth Deer.

There is no singularly authoritative definition of Indigenous Peoples under international law. Many Indigenous Peoples populated territories before the arrival of others and often retain distinct cultural and political characteristics, including autonomous political and legal structures.

UN Human Rights recently issued a Stocktaking report on Indigenous Peoples participation at the UN, which compiled existing procedures on their participation, highlighting prevailing gaps and good practices.

“The report recommends that the Human Rights Council and other UN bodies create structures to support Indigenous Peoples’ participation without requiring something called ‘ECOSOC consultative status’,” said Hernán Vales, Chief of the Indigenous Peoples and Minorities Section at UN Human Rights. ECOSOC stands for Economic and Social Council.

And Vales noted that Indigenous Peoples voices are crucial in advancing their human rights and participation in international decision making.

“The inclusion of Indigenous Peoples empowers them to advocate for their rights, influence policies that affect them, and support holding States accountable to international human rights standards,” he said.

“

It's important to keep States, governments and corporations in line with international human rights law or with the simple fact that it exists and that we have rights.

“

Kenneth Atsenhaienton Deer, Indigenous Peoples’ rights advocate

Some steps have been taken towards ensuring the participation of Indigenous Peoples, for the first time in the history of the Human Rights Council, Indigenous Peoples will be able to attend without needing to be organized as an NGO.

Becoming Peoples

In the 70s, Indigenous Peoples wondered where were their rights in the newly emerging international human rights framework, said Deer. Their concerns included protection of their languages and territories, and the right to self-determination.

“If you see how the human rights instruments were being written and designed and implemented, they did not have Indigenous Peoples in mind,” Deer said.

For example, Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, states “all peoples have the right to self-determination” and so they can freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development. However, the Indigenous were not considered “peoples”.

“[At the UN] we were basically informed that international law did not apply to us, which was just astounding to hear,” Deer said. “[They told us] that we were populations, communities, tribes and that the UN did not recognise us as “peoples” with the right to self-determination.”

“Authors of the original framework of human rights did not take into account the distinct status, rights, and role of Indigenous Peoples, our distinct cultural context,” added Dalee Sambo Dorough, an Inupiaq from Alaska, senior scholar, and special advisor on Arctic Indigenous Peoples at the University of Alaska in Anchorage.

Dorough is a member of the EMRIP and former chair of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. She also helped draft the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

For Dorough, underlying that original human rights framework was the Western European ideology the world, which was permeated by notions of cultural and racial superiority, tainted by the accompanying colonialism.

“Human rights saturate everything. We're all human beings. And in the case of Indigenous Peoples, human rights attach to our collective relationships, including the right of self-determination and our rights to lands, territories, and resources,” she said.

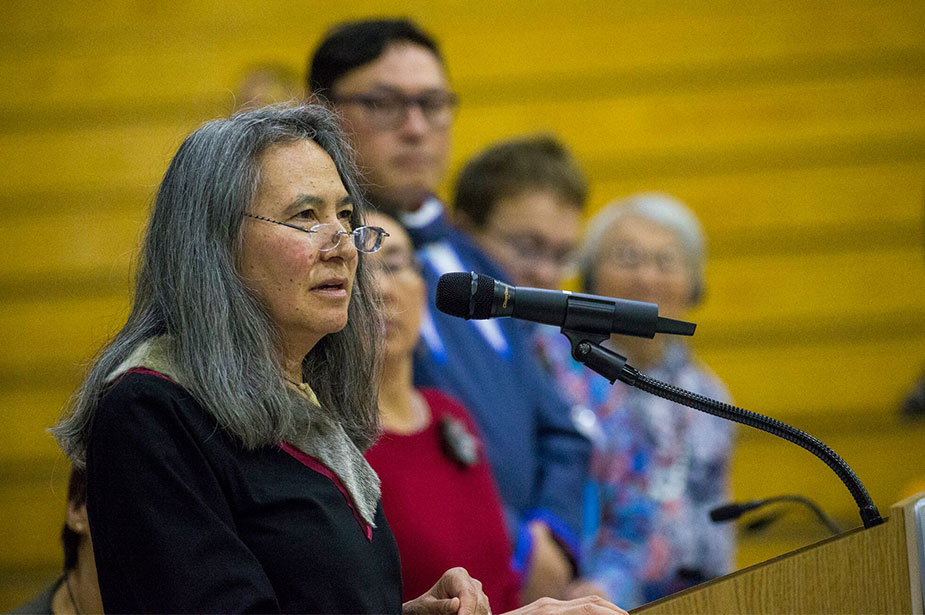

Dalee Sambo Dorough delivers a speech upon election as the Chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, 2018. © Bill Hess

In 2007, the distinct cultural context of Indigenous Peoples was more fully accommodated with the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration affirmed their right to self-determination consistent with international law and the international human rights framework.

“

Every struggle, every triumph and every positive move that has been made by Indigenous Peoples, has helped to lighten the load for the next generation.

“

Dalee Sambo Dorough, member of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

For Dorough, now that the human rights framework and tools are finally in place, a crucial challenge remains.

“How do we exercise these important, fundamental rights? UN member States and all others, even our own people, need to understand what it means to exercise and enjoy the right of self-determination within and outside of our own communities,” Dorough said.

In addition, not all Member States have implemented the Declaration. According to Deer, some of the reasons include the desire to retain territorial control, to have unlimited access to natural resources, and the racism that persists towards Indigenous Peoples as a legacy of colonization.

The Stocktaking report made a number of recommendations to Member States to increase participation including establish an accreditation mechanism for Indigenous Peoples’ participation at the UN, increase funding for their participation at the UN, prevent intimidation and reprisals, and facilitate visa processes to strengthen participation, among others.

“Overcoming the challenges means creating the intellectual and political space for Indigenous Peoples to enter and to think about how our rights, our collective human rights, have to be accommodated by every system,” Dorough said.