OHCHR and freedom of expression vs incitement to hatred: the Rabat Plan of Action

The Rabat Plan of Action

The Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence brings together the conclusions and recommendations from several OHCHR expert workshops (held in Geneva, Vienna, Nairobi, Bangkok and Santiago de Chile). By grounding the debate in international human rights law, the objective has been threefold:

- To gain a better understanding of legislative patterns, judicial practices and policies regarding the concept of incitement to national, racial, or religious hatred, while ensuring full respect for freedom of expression as outlined in articles 19 and 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR);

- To arrive at a comprehensive assessment of the state of implementation of the prohibition of incitement in conformity with international human rights law and;

- To identify possible actions at all levels.

The Rabat Plan of Action was adopted by experts at the wrap-up meeting in Rabat on 4-5 October 2012.

Download the Rabat Plan of Action

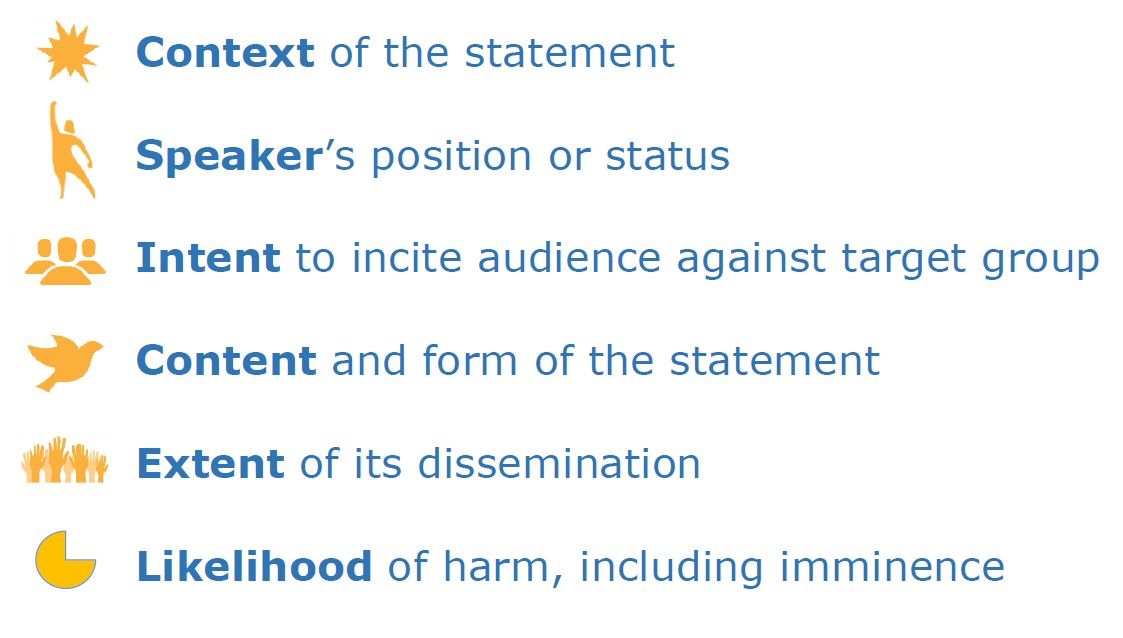

A high threshold for defining restrictions on freedom of expression

Across the world there are two extremes: on the one hand, 'real' incitement cases are not prosecuted, while on the other hand peaceful critics are persecuted as 'hate preachers' (see the related webstory). The Rabat Plan of Action suggests a high threshold for defining restrictions on freedom of expression, incitement to hatred, and for the application of article 20 of the ICCPR. It outlines a six-part threshold test taking into account (1) the social and political context, (2) status of the speaker, (3) intent to incite the audience against a target group, (4) content and form of the speech, (5) extent of its dissemination and (6) likelihood of harm, including imminence.

Download the one-pager on the Rabat threshold test

Rabat threshold test in action

The Rabat threshold test is being used by the national authorities for audio-visual communication in Tunisia, Côte d’Ivoire and Morocco. Furthermore, in its judgment of 17 July 2018, the European Court of Human Rights referred to the Rabat Plan of Action under relevant international materials as well as in its summaries of submissions from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Article19. The United Nations peacekeeping operation in the Central African Republic is applying the Rabat test in its monitoring of incitement to violence. The UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, which was launched in June 2019, also refers to the Rabat Plan of Action (see also the Detailed Guidance on Implementation for UN Field Presences.

In August 2019, the High Commissioner addressed the Security Council in an Arria-formula meeting on advancing the safety and security of persons belonging to religious minorities in armed conflicts. In this context, she reiterated that the Rabat Plan of Action emphasizes the role of politicians and religious leaders in preventing and speaking out against intolerance, discriminatory stereotyping and instances of hate speech. In October 2021, Access Now stressed in another Arria-formula meeting that “any restriction on social media must reflect the U.N. Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech and the excellent Rabat Plan of Action.”

At the regional level, the policy guidance by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights on “Freedom of Religion or Belief and Security” also encourages States to train law enforcement officials and the judiciary to understand and apply the six-part test set out in the Rabat Plan of Action (context; speaker; intent; content or form; extent of the speech; and likelihood of harm occurring, including imminence), in order to determine whether the threshold of incitement to hatred is met or not.

The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression recommended companies to adopt content policies that tie their hate speech rules directly to international human rights law, indicating that the rules will be enforced according to the standards of international human rights law, including the relevant UN treaties and interpretations of the treaty bodies and special procedure mandate holders and other experts, including the Rabat Plan of Action. While its six-part test is applicable to the criminalization of incitement, the Special Rapporteur noted that those six factors should have weight in the context of company actions against speech as well since the factors “offer a valuable framework for examining when the specifically defined content – the posts or the words or images that comprise the post – merits a restriction”. Since 2021, Meta’s Oversight Board referred in several decisions to the Rabat Plan of Action, using its six factors to assess the capacity of speech to create a serious risk of inciting discrimination, violence or other lawless action.

In 2024, the High Commissioner highlighted the Rabat Plan of Action as detailed guidance in distinguishing between permissible speech and speech that incites discrimination, hostility and violence. Furthermore, the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief recommended that incidents should be assessed carefully, on a case-by-case basis, with the benefit of the guidance of the Rabat Plan of Action (A/HRC/55/74). In this context, the “Faith for Rights” framework also builds upon the Rabat Plan of Action, focussing specifically on the human rights responsibilities of faith actors. The #Faith3Rights toolkit provides practical peer-to-peer learning modules, including on addressing incitement to hatred and violence in the name of religion.