Honduras passes historic law to protect the environment

14 August 2024

The scorching heat beats down the small dirt roads of the community of Guapinol in northern Honduras, a community of 3,000 people whose livelihood depends mainly on agriculture, livestock, and remittances from relatives in the United States.

Surrounded by African palm plantations, the Guapinol River is slowly returning to being a source of shade and clean, clear water, as it had always been until 2018, when people realised that the water became heavily polluted.

“Water looked like chocolate; it was oily. To us, it was unusable, dirty, and it was also an alert that we needed to organize ourselves and look for the reason why our river was dirty,” said Juana Zúniga, an environmentalist and human rights defender, during an interview in her home.

Zúniga, along with her life partner José Cedillo, a human rights defender, environmentalist and victim of arbitrary detention, have fought for the human right to a healthy environment.

Shortly before they realised the water was dirty, a company started mining in the nearby “Botaderos” National Park “Carlos Escaleras Mejía,” named after a Honduran environmentalist who was murdered in 1997.

A mining company operating at the ‘Botaderos’ National Park, ‘Carlos Escaleras Mejía’, near Guapinol, Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

The Park had been declared a natural protected area by the government in 2012. However, through a process full of irregularities documented by UN Human Rights, in 2013 the protected area was reduced, which in turn allowed companies to be licensed to exploit it.

In response to this, the Guapinol Community Environmental Committee was created, with 42 members, including Zúniga and Cedillo.

“We started to raise people's awareness, to look for answers as to why our river was polluted. We started protests too and sit-ins at the municipality, taking over the streets,” Zúniga said.

“The case of the Guapinol community is an emblematic one because of the serious impact that an extractive megaproject has had in the Botaderos National Park ‘Carlos Escaleras Mejía’,” said Isabel Albaladejo Escribano, UN Human Rights Representative in Honduras. “The mining activities in this Park have entailed human rights violations against the affected communities and serious damage to the environment and to natural resources.”

In addition to the environmental risks, the people who demonstrated against the mining operations faced attacks. Thirty-two human rights defenders were criminalised because of their peaceful exercise of the rights to freedom of expression and association.

Fighting for freedom

The defenders spent two and a half years in pre-trial detention and included: Jeremías Martínez Díaz, José Daniel Márquez Márquez, Kelvin Alejandro Romero Martínez, José Abelino Cedillo, Porfirio Sorto Cedillo, Orbín Nahúm Hernández, Arnold Javier Alemán and Ewer Alexander Cedillo Cruz. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention stated in an opinion that they were arbitrarily detained.

“These comrades were being unjustly imprisoned and for us it was a change in our lives,” Zúniga said. “I had to take the responsibility to stay with my daughters, but also to go on, to go from being a housewife to being at the forefront and show how the government and the company were being corrupt.”

“It was a constant struggle,” she said. “Almost three years of being in the courts, in the Public Prosecutor's Office, in sit-ins, advocating for these comrades to be released. The struggle strengthened women's empowerment, also here in the community.”

While the Guapinol Community Environmental Committee was honoured in Washington D.C. at the Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award, the defenders were being attacked and vilified in Honduras. This Award aims to recognize human rights defenders throughout the Americas who fight for economic, cultural, social, and civil rights.

“It was difficult for us to know we come from a country where our rights are violated, where we were being imprisoned and murdered and, in another country, we were being awarded,” Zúniga said.

José Cedillo, a human rights defender and environmentalist in Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

The right to a healthy environment

Throughout this time, UN Human Rights in Honduras supported the defenders and their families in their fight for justice. Finally, in February 2022, the defenders regained their freedom.

“The first thing I did [upon leaving prison] was to thank God and hug family, friends and all those who had fought for us, because there was a crowd of people outside waiting for us, it was a blast at that moment, our freedom,” said Cedillo.

The fight didn’t end with the freedom of the defenders though. The company was still operating, and the water was still being polluted. In the aftermath of the liberation, some defenders had to leave Guapinol for safety reasons, and were forcibly displaced.

Despite the end of the judicial process, defenders continued to face attacks, including smear campaigns, threats and even killings.

Zúniga and Cedillo stayed in Guapinol and continued to fight for their community's right to a safe and healthy environment. The struggle continued, but now the goal was to regain the freedom of the park.

“UN Human Rights, in coordination with the affected communities, has pushed several legal and advocacy actions before the competent authorities of the Executive and Legislative branches, providing advice and technical assistance to resolve the environmental problems in the area and the human rights violations of the affected communities,” Albaladejo Escribano said.

Over the last two years, the Office has been working collaboratively with the Guapinol defenders and providing technical assistance to the National Congress to pass an historical law, the Executive Decree 18-2024.

This law re-establishes the original layout of the National Park and, in addition, ensures the effective protection of all protected areas in Honduras by prohibiting the granting of mining rights in declared protected areas, declared water-producing zones, and in beaches and low sea areas declared as tourist areas. The law was recently approved and published.

“

UN Human Rights has always been close to the Guapinol case and supported us with advocacy actions, always calling the competent institutions.

“

Juana Zúniga, Environmental human rights defender

“For us who have sustained a struggle that has brought forced displacements, which has left three dead in this community, 32 comrades criminalised, eight of them deprived of their freedom for 914 days, the approval of the decree is a great achievement,” Zúniga said. “It is a major breakthrough that this park will enjoy freedom.”.

“Although with the approval of the law, some government institutions have begun the process of cancelling mining concessions granted in the core zone of the National Park, there are still challenges for the communities, especially with regard to the protection of environmental defenders,” Albaladejo Escribano said.

According to UN Human Rights, one of the main challenges regarding the implementation of the law is to ensure that the restoration and conservation processes of the National Park and other protected areas affected by extractive projects are effective, and that they include the active, free, effective, informed and meaningful participation of the affected communities.

Life by the river

Juana Zúniga, a human rights defender and environmentalist in Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

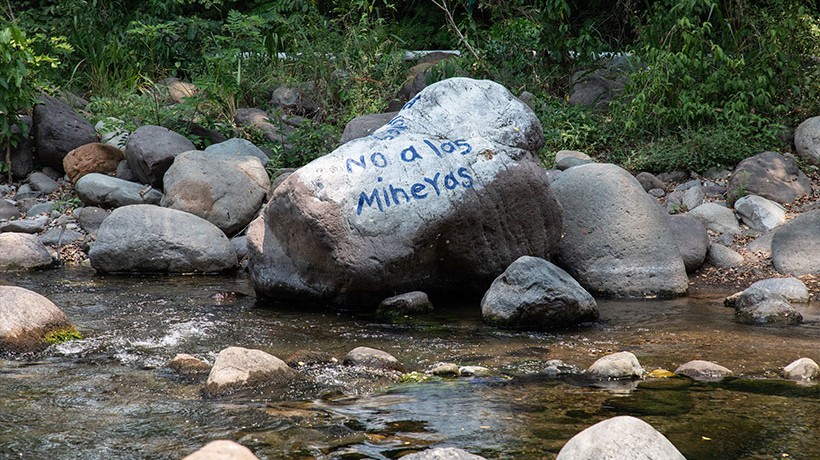

“No to mining companies” written in Spanish in stone in the Guapinol River, in Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Juana Zúniga and her daughter in Guapinol river in Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

José Cedillo, a human rights defender and environmentalist in Honduras stands in a rock watching the Guapinol river. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

View of a recovered part of the Guapinol river in Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Juana Zúniga and a UN Human Rights staff member walk on what used to be part of the Guapinol river. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Juana Zúniga in the middle of what used to be part of the Guapinol river. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Mining company operating near the Guapinol river. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

The Office, through its presence in Honduras, will continue to assist the country and the affected communities to ensure that the implementation of the law is done comprehensively and in line with human rights standards.

“The conservation, protection and sustainable use of natural resources so that the human right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment have to be guaranteed, as it’s a fundamental element to address the impacts of climate change on the Honduran population,” Albaladejo Escribano said.

According to Zúniga, the work and support of the Office in Honduras has been key for them.

“They are part of the reason why the case is where it is now,” Zúniga said. “They have helped our park to be freed. We were dealing with a monster.”

Aerial view of an African palm plantation near Guapinol, Honduras. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau