Mexico’s disappeared: Pain serves as an engine for collective struggle

30 August 2024

It was early on a Friday morning in Tepotzotlán, in the central State of Mexico, and María Herrera Magdaleno’s kitchen was already filled with the aroma of home-cooked stews and casseroles.

Affectionately known as Doña Mary, Herrera Magdaleno was preparing a feast to help with the long day search for disappeared persons. She’s looking for her own children, Raúl and Jesús Salvador who disappeared in 2008 and Luis Armando and Gustavo in 2010. Her other sons Juan Carlos and Miguel Angel Trujillo Herrera also came along to support the search.

“This situation is one of the most terrible things that can happen to a human being. You see me calm, but as soon as the image of my children comes to my mind, I start to remember from the moment I had them in my womb,” Herrera Magdaleno said.

After tirelessly going to government institutions without finding any answers, Herrera Magdaleno and her sons joined the fledgling social movement for justice and peace in Mexico.

“I watched with great pain and sadness as thousands of families took the streets with photographs in hand, looking for their parents, their siblings, their children, grandmothers looking for their grandchildren,” Herrera Magdaleno said. “It was something terrible and I said to myself, well, we have to do something.”

María Herrera Magdaleno holds the poster depicting images of her disappeared children in her home in Tepotzotlán, State of Mexico. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

In 2013, the Trujillo Herrera family, despite many economic restrictions, created the group ‘Familiares en Búsqueda María Herrera’ (Relatives in Search ‘María Herrera’) and launched the ‘Red Enlaces Nacionales’ (National Links Network), which currently brings together 190 collectives from all over the country.

“First we started meeting in a small park because we had no place to meet,” said Herrera Magdaleno. “Now we've just been given a space that can hold 3,000 people or more.”

The organisation of collectives to search for disappeared persons in Mexico has grown exponentially in the last 15 years, along with the number of cases of disappeared persons.

Official records in Mexico indicate that there are currently 115,000 people whose whereabouts are unknown. According to the official available information, the highest concentration of disappearances occurred from 2006 to date, which coincides with the beginning of the ‘war on drugs.’ A smaller percentage is centred on the 1970s and the 1980s, during the ‘Dirty War,’ in which enforced disappearances were used as a strategy of repression against political dissidents.

According to UN Human Rights, some of the main challenges are widespread impunity, deficient institutional capacities to search for people, limited institutional coordination and collaboration, insecurity and the risks faced by human rights defenders, including searchers, as well as the forensic crisis.

“The absence of a human rights-based security policy is one of the greatest challenges to the prevention of criminal behaviour and effective investigation and prosecution,” said Jesús Peña Palacios, Deputy Representative of UN Human Rights in Mexico.

In this context, the Office in Mexico carries out comprehensive work to advance the fight against the disappearance of persons, which includes, among other actions, accompanying victims, relatives, and collectives; providing technical advice to State authorities and institutions; aiding civil society organisations; supporting the implementation of international recommendations; and increasing the visibility, dissemination and awareness-raising of the problem.

Widespread disappearances, collective struggle

“In 2007, the first cases of disappearances began to occur, with mothers saying, ‘my son was taken away, my son has not appeared,’” said Consuelo Morales Elizondo, a human rights defender and Catholic nun from the northern Mexican state of Nuevo León, affectionately known as Sister Consuelo. “The first cases were of police officers, and we began to see that organised crime, in alliance with the authorities, was disappearing people.”

More than 30 years ago, Morales Elizondo founded the organisation, Ciudadanos en Apoyo a los Derechos Humanos (CADHAC, Citizens in Support of Human Righs), in Monterrey, the capital of Nuevo León.

“The disappearance, from my point of view, cannot happen without the consent or complicity of the authorities and responds to economic and territorial interests,” Morales Elizondo said. “Our politicians somehow allowed themselves to be corrupted, in such a way that crime permeated State institutions.”

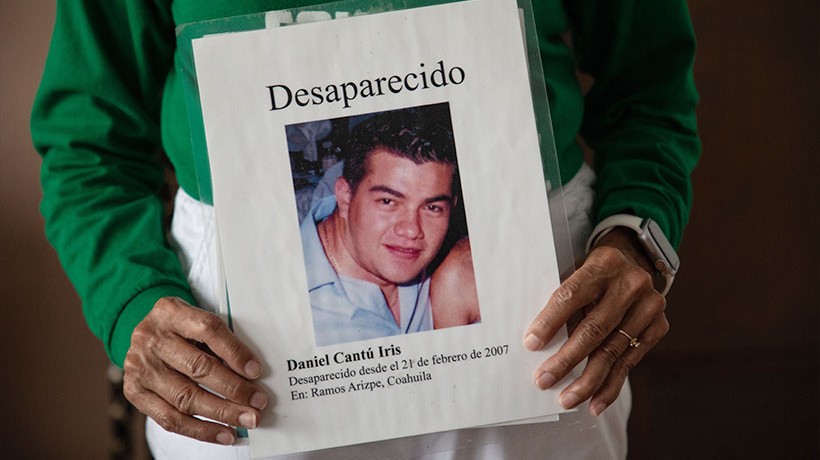

Another family’s struggle begun in 2007, in the state of Coahuila, when Daniel Cantú Iris was disappeared.

“Daniel is a very talkative boy, a great dancer, very cheerful,” said Diana Iris García, Daniel's mother, and a human rights defender and member of Fuerzas Unidas por Nuestros Desaparecidos (United Forces for Our Disappeared) in Coahuila, Mexico. “He likes sports very much. He has been cycling since he was ten years old and was a national champion for Coahuila.”

In her home, Diana Iris García, a human rights defender from Coahuila, Mexico, continues to search for her son Daniel Cantú Iris. Her shirt says in Spanish, Where are they? Looking for them tirelessly. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Iris García explained that working collectively means walking and thinking collectively. The search for missing persons requires mutual support both because of the difficulties they face in terms of access to justice, but also because of the pain of not knowing the whereabouts of a loved one, she added.

“

This struggle is very, very painful, but it is a struggle based on love, and that love is what sustains us.

“

Diana Iris García, Human Rights Defender and mother of Daniel Cantú Iris

Faced with ineffective government action, families like those of Herrera Magdaleno and Iris García took the search for their loved ones into their own hands more than a decade ago, prioritizing search efforts focused on finding them alive.

The people who search for the disappeared, who are mainly women, in practice have become forensic experts as well, identifying the type of soil, the humidity, the smells. In addition to this, they receive tips, often anonymously, about the possible location of bodies, and coordinate field searches and support each other.

Until they are found

María Herrera Magdaleno, a human rights defender and a mother searching for her sons, prepares food in her kitchen for the day's search in Tepotzotlán, State of Mexico. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

The group preparing for the start of a search day in Tepotzotlán, State of Mexico. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

A search group and members of UN Human Rights stand together after the discovery of a body in the state of Querétaro, Mexico. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Yadira González, who is looking for her brother Juan and is a human rights defender and founder of Desaparecidos Querétaro, and a member of the group react to the discovery of a body in a clandestine grave in the state of Querétaro. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Sister Consuelo Morales Elizondo, a human rights defender in the state of Nuevo León, Mexico. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Diana Iris holds the photo of her disappeared son Daniel Cantú Iris, in the state of Coahuila. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Photographs of disappeared people on a wall at the organisation, Ciudadanos en Apoyo a los Derechos Humanos, in the state of Nuevo León. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

A group of members from the collective AMORES de Nuevo León, supported by the civil society organisation Ciudadanos en Apoyo a los Derechos Humanos. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

Human rights in action

“UN Human Rights in Mexico brings to the table credibility and a consistent and constructive perspective that ignites confidence in authorities and victims,” Peña Palacios said. “This is reflected in the facilitation of dialogue or rapprochement between them. Cooperation is promoted in complex situations as well, to achieve solutions and to influence the improvement of institutional responses.”

The impact of the Office in Mexico includes the strengthening and implementation of the legal framework on disappearances, the promotion of the creation of dialogue mechanisms, the facilitation of the visits of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances in 2011 and of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances in 2021 and the subsequent advocacy for the implementation of their recommendations and observations, and the visibility of the struggle of families searching for their loved ones.

“The Office has not left us alone and for us it has been like legitimising our struggle and a fundamental ally in our demands,” Iris García said.

A UN Human Rights staff member talks to María Herrera Magdaleno about her disappeared children in Tepotzotlán, State of Mexico. © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

“

The High Commissioner's team has been with us during the most critical moments here in Mexico.

“

Sister Consuelo Morales Elizondo, human rights defender

In his vision statement, “Human Rights: A Path for Solutions,” Volker Türk, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, stated that widespread impunity needs to be urgently addressed and that good governance depends on holding accountable those responsible for human rights violations.

“Beyond an individual remedy, access to justice plays a broader, crucial role: preventing the simmering of unaddressed grievances capable of triggering instability and conflict,” Türk said. “It is in every State’s interest to invest properly in institutions that support the rule of law.”

“Society has to show solidarity because it can happen to anyone, and we don’t want this to happen to anyone else. Justice must be built and with it, peace,” Iris García said.

“

The voice of the victims is the cornerstone for any change in a country hurt by its own violence. They are the main engine towards truth and justice.

“

Jesús Peña Palacios, UN Human Rights Representative in Mexico

A heart-shaped pendant that says, We are looking for you because we love you! © OHCHR/Vincent Tremeau

International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearance