Chile’s constitutional process: an historic opportunity to enshrine human rights

08 June 2022

As a 10-year-old girl growing up in Chile’s Araucanía region, Elisa Lonconwalked an hour on a dirt road to get to school, and another hour to get back home. Sometimes a passing bus would pick her up, making the 8-km journey easier. Despite the hardship, Loncon considered herself lucky; she had shoes, while her mother walked barefoot and got blisters.

Loncon, who belongs to the Mapuche indigenous community, was elected the first president of Chile’s constitutional assembly, the body charged with writing the country’s new constitution.

“Never before have the indigenous communities of Chile been invited to help draft a new constitution,” said Loncon, who to support her family sold vegetables at a local market and went on to become a linguist and professor at the University of Santiago, having obtained two doctorate degrees.

“For the first time in our history, Chileans from all walks of life and from all political factions are participating in a democratic dialogue,” she added.

The Chilean constitutional process represents a defining moment for the South American nation. Written by a constitutional assembly with an equal proportion of women and men, the draft enshrines human rights and values for a more equal and inclusive society, with special attention to groups that have been historically excluded and protection of economic and social rights.

The draft for the new constitution was written by a constitutional assembly with an equal proportion of women and men. REUTERS/Ivan Alvarado

The constitutional process is receiving the assistance of the UN Human Rights Regional Office for South America. Under the project “Chile: human rights at the centre of the new Constitution,” the assistance has included webinars, public hearings with the assembly’s different committees and civil society groups, and the publication of a series of short, clear and accessible documents that summarise the international framework for human rights.

The 27 documents focus on specific human rights, prohibitions and vulnerable groups, from access to justice and the rights to reparation to the human rights of women, Afro-descendants and LGBTI people.

Jan Jarab, the UN Human Rights regional representative for South America, said the draft of the new Chilean constitution integrates the standards of international human rights law.

“The constitutional process is a space conducive to trust and hope and to establish the foundations that can sustain a more equal and fair country.”

A constitution born from a social “upheaval”

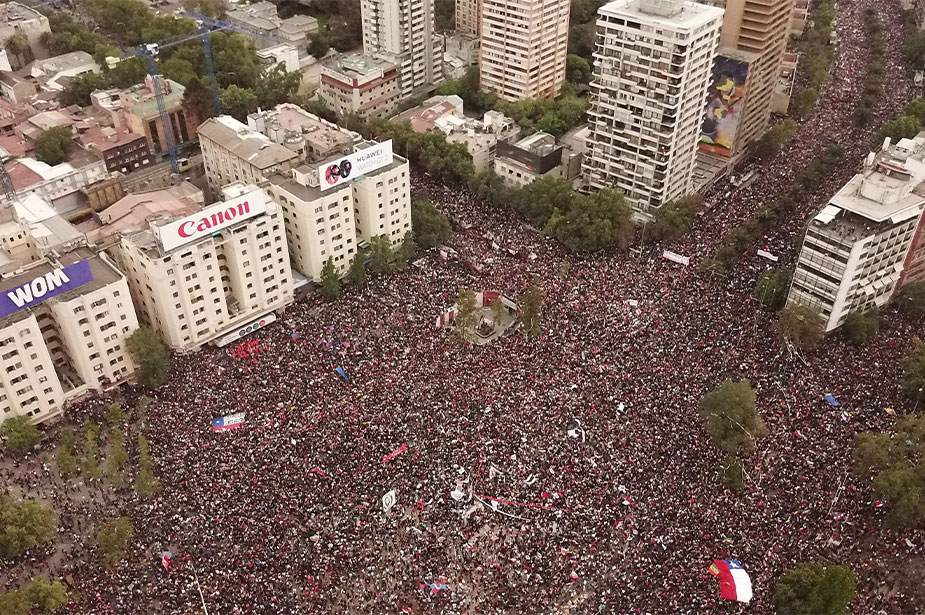

The constitutional process is the result of a broad national agreement among political parties in Chile to end a wave of popular protests against inequality and poor public services that erupted in October 2019. Millions of Chileans filled the country’s streets and public squares to demand change.

Known as the estallido social, or social upheaval, the protests were a cry for more justice and more dignity for all people, as well as a denunciation of deep economic and social inequities. One year after the protests started, Chileans voted overwhelmingly in favour of drafting a new constitution, and in a later ballot voted for the 155 members of the constitutional assembly.

Millions of Chileans filled the country’s streets and public squares to demand change. REUTERS/Ivan Alvarado

Marcela Guillibrand, of the civil society group Ahora Nos Toca Participar (It is Now Time to Participate), said the new constitution offers Chile an opportunity to overcome structural injustices, reaffirm its commitment to human rights and chart a path for a sustainable and inclusive development that leaves no one behind.

“

Our current constitution falls short of meeting the social and economic demands of Chileans and does not reflect today’s society in all its diversity.

“

Marcela Guillibrand, of the civil society group Ahora Nos Toca Participar

“In terms of equality and human rights, the draft represents an enormous step forward and includes many of the profound changes that Chileans have been demanding for years.”

Democratic participation

The constitutional process is unprecedented for its participatory mechanisms, which has allowed the involvement of communities historically discriminated against, said Valentina Contreras, the Chilean representative for the civil society organisation Global Initiative for Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (GI-ESCR).

Contreras said the constitutional draft is the result of a broad and diverse dialogue within the representative body. Among other things, the draft increases autonomy for indigenous territories, expands environmental rights and makes fighting climate change a constitutional duty for the state.

“Human rights are the common thread of the constitutional process,” Contreras said.

The rights of indigenous people are included for the first time in the draft constitution, Loncon said. Indigenous peoples’ rights are absent in the current charter. Of the 155 seats on the constitutional assembly, 17 were reserved for indigenous peoples.

For Loncon, the constitutional process is a unique opportunity for Chile to satisfy a historical debt with indigenous communities and to establish a new social contract based on the respectful coexistence of the country´s different national and cultural groups.

A national referendum to vote on the new constitution is set for 4 September. If approved, it would replace the current charter, which was written in 1980 under the 1973-1990 military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, although it has undergone several changes.

“Hope is returning to human beings,” Loncon said. “What we are seeing is a human dream.”