Report: We must join forces to combat enforced disappearances in Mexico

25 April 2022

A mother escorted her daughter to a prison in Mexico to visit her partner. She watched her walk into the prison, but she never came out. When she consulted prison authorities, they claimed they didn’t have any information about her. She’s still disappeared.

This story is just one example of the cases that are referred to in a new report by the Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) following its visit to Mexico last November. The report includes the Committee’s findings, which reveal the extreme breadth of the disappearance problem in the country, along with trends and recommendations.

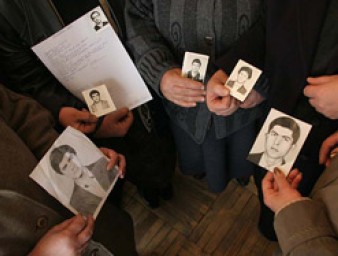

According to the National Registry of Disappeared Persons in Mexico, 99,249 missing persons are registered. Out of these, 112 were reported as disappeared during the two weeks of the Committee’s visit.

“The Committee appreciates the State's openness to dialogue, as well as the willingness of all involved to provide particularly valuable information and documentation,” said Carmen Rosa Villa Quintana, Chair of the Committee, during the launch of the report at the 22nd session of the CED. “We thank the families and relatives of the disappeared for their testimonies, perspectives and proposals and to publicly highlight their daily struggle.”

To compile such a comprehensive assessment, members met with authorities and hundreds of victims, groups, and civil society organisations and visited prisons, migrant holding centres, and accompanied exhumations and search days.

Findings and trends in disappearances

According to the report, more than 52,000 unidentified dead people currently lie in mass graves, forensic facilities, universities, and forensic protection centres.

“This figure, despite its magnitude, does not include the bodies not yet located, nor the thousands of fragments of human remains that families and search commissions collect weekly in clandestine graves,” the report states.

“

Disappearances continue to target most men between the ages of 15 and 40

“

There is an increase in the number of disappearances of children, adolescents, and women, which was made more prevalent during the COVID 19 pandemic.

The report highlights the concern about the victimization of women who are often left to take care of their families and search for their loved ones with the financial burden of both responsibilities.

Women end up “suffering the serious social and economic effects of disappearances and, in addition, in many cases are victims of violence, persecution, stigmatization, extortion and reprisals.”

There are many other victims who are impacted including journalists, human rights defenders, migrants, and indigenous people. For indigenous people, their disappearances usually take place in the context of territorial conflicts associated with the mining or energy projects or land grabbing for economic exploitation by organized crime groups, with different degrees of involvement or compliance of State agents.

The Committee also found information on the disappearance of LGBTIQ+ persons by security forces or organized crime groups for the purpose of social cleansing or sexual exploitation, mainly after they have been forced to enter reconversion centres.

Holding the perpetrators accountable would seem straightforward, but impunity is a recurring trend in Mexico and results in the lack of trust of victims in institutions result in a high number of unreported cases, the report states.

“Impunity in Mexico is a structural feature that favours the reproduction and cover-up of enforced disappearances and endangers and causes anxiety to the victims, to those who defend and promote their rights, to public servants who search for disappeared persons and investigate their cases and to society as a whole,” the report states.

Steps for prevention and eradication

The Committee urges the State to address all the report’s findings and create a national policy for the prevention and eradication of enforced disappearances. The design of the policy should involve all federal, state, municipal authorities, the autonomous bodies of Mexico and civil society, including victims and groups of victims.

Other recommendations include the urgency to eliminate the structural causes of impunity and to hold people accountable in the disappearances and stress the urgency to abandon the militarization approach to public security, spread awareness about disappearances in Mexico for people to know how to report such cases to authorities, and develop a comprehensive training program on disappearances.

The report pushes for the policy to contain concrete actions and indicators that ensure its compliance and results to be evaluated. An independent monitoring system must be created to ensure accountability.

One victim, who spoke with Committee members, recalled how impunity and the lack of access to information about disappearances in the country has impacted her life.

"I had never imagined being here with you talking about my mother's disappearance,” she says. “I didn't think this existed or that it could happen to me. It's not the kind of thing you're taught in school. When your mom suddenly disappears, you have no idea what to do. It's a nightmare that restarts every day."

The Committee considers this report as an opportunity for change in Mexico and insists on its commitment to support the process of implementing their recommendations towards the eradication and prevention of enforced disappearances in Mexico.

“Disappearance of persons in Mexico is everyone's problem: of society as a whole and of all humanity,” says the report.