Against All Odds: The Making of a Lenca Youth Leader

28 February 2023

By 23, Diego Rafael Osorto had expected to be “en el Norte” – in the North, like the hundreds of other Hondurans who start their trek towards the Texas border every morning.

Instead, his clean, even brush strokes spread layers of paint across a wood sculpture, helping transform his passion for art into a socially responsible business.

On the surface, his decision to stay in one of the Western Hemisphere’s poorest countries may fly in the face of logic. Unemployment is high, corruption is endemic, and there is plenty of violence, especially gang violence punctuated by extorsion and murder. Adding to the country’s misery was the Covid-19 pandemic and two devastating hurricanes in 2020. The inability of the state to provide its people with a decent living prompted them to elect a more socially responsible government in 2021.

Diego, too, had thought of leaving.

His father emigrated when Diego was born, and Diego grew up starry-eyed, with dreams of the North dangling like glittering promises of success and riches. The lack of work and opportunities and the high suicide rate among young people fueled his yearning to leave.

“It scared me as a young person, I felt hopeless.”

He had little to look forward to in Honduras, having grown up in poverty and without a support network.

“As a child, my mother was very ill, and I was often moved from one home to another while she was in treatment. This marked me for life. Often, I didn’t even know where my mother was.”

His mind may have wandered northwards, but reality would abruptly pull him back whenever he thought of the women in his life.

“The women – my mother, my grandmother, all of them – taught us the value of life, and they were my inspiration. They fought so hard to survive. How could I leave them behind?”

The imperative of income

To stay in Honduras, Diego needed a way to survive. He quit school and started working two jobs back-to-back, one of them in a café. It seemed innocuous at the time, but it transformed his life.

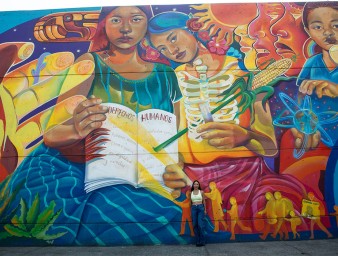

Diego Osorto, painting at home in La Esperanza, department of Intibuca, Honduras ©OHCHR Honduras

As he observed how the café was run, he began thinking of starting his own business. He won a scholarship for a business development training course, and learned the basics of entrepreneurship, like marketing and how to develop a business plan.

Soon, he would discover a new passion.

“I saw a piece of wood and I felt it needed something on it, so I painted it. Then I discovered a new technique of painting from my brother, who works with mosaics. And then one day someone offered to buy my art and I discovered that you could earn an income from it.”

Growing up, his grandmother had cooked and sold her food to help feed their family.

“Some days we had no food and not enough money to buy it. So my grandmother cooked what she could and now, at 70, she still makes the best food. If tourists had a chance to try it, they would love it!”

Business, art, gastronomy: could this ambitious vision materialize?

An idea is born

It was a time of renewal in Honduras – a woman had been elected president for the first time, a ray of hope for the country’s many underrepresented groups. So when Diego joined a workshop by ParticiPaz, a joint project by UN Human Rights and the UN Development Program, a new world opened for him.

“I heard about human rights for the first time,” he said. “The theme was discrimination, which is very strong here, against indigenous people but also against women. I learned how I as an artist can advocate in my community for the protection of human rights defenders, and even become a human rights defender myself.”

The project, financed by the UN Peacebuilding Fund, helps reduce conflict by encouraging communities who often lack representation to take part in governance decisions.

And it gave Diego an idea.

He approached UN Human Rights in Honduras and suggested creating a space for community workshops: the UN could use his space, and so could the community. Together, they would work to fight discrimination against indigenous people, defend their land against encroachment by big business, and fight the delinquency that was slowly poisoning his country’s youth – all the while encouraging young indigenous people to stay in the country.

A cultural revival

Road to La Esperanza, Intibucá, Honduras © OHCHR Honduras

Aerial view of La Esperanza, department of Intibucá, Honduras © OHCHR Honduras

Liquidambar's sign, art center and coffee shop, project by Diego Osorto, in La Esperanza, department of Intibuca, Honduras © OHCHR Honduras

Omar Vasquéz playing the guitar at Diego Osorto's house, in La Esperanza, department of Intibuca, Honduras © OHCHR Honduras

Diego lives in La Esperanza, a busy state capital in southwestern Honduras with a reputation for cold weather, the coldest in the country. In the morning, a white fog rises over the mountain plateaus of Intibucá province, where indigenous Lenca have lived for 1500 years. The snow-like blanket covers the lakes and trees with a soft white cloud until the sun pierces through and burns it off.

La Esperanza – which means “hope” in Spanish – is a market town for the rural Lenca who come here to sell their produce. It is also known as the birthplace of Berta Cáceres, the prize-winning environmental activist who was assassinated in her home in 2016 after successfully fighting to stop the building of a dam.

La Esperanza sits right on the Ruta Lenca, the Lenca Trail, a tourist itinerary that winds through Lenca lands and encourages visitors to discover Lenca culture – their way of life, their bold hand-woven textiles and their delicate black-and-white pottery.

Until recently, Lenca culture was in retreat, its language almost extinct, its young people seeking a livelihood elsewhere. But there is a move afoot in Honduras to revitalize indigenous cultures, and the Lenca Trail is part of that revival.

“There is more pride now, people are more conscious, especially through social media,” said Diego. “I say, let’s be orgullosos of our Lenca culture, let’s be proud of it. Let’s support ourselves locally and share our food and our handicrafts with people.”

Diego wants to be part of this revival.

A cultural corridor

Armed with little more than passion and new marketing knowledge, he decided to turn his mother’s garden into a café. And exhibit other people’s art. And serve food. He decided to name it Liquidambar, after a popular tree, one of the country’s leading exports.

“My business will be a vehicle for advocacy for all, all races, all genders, that’s something I learned from the ParticiPaz workshop.”

UN Human Rights sees in Diego a promising young leader. “He has such positive leadership,” said Eloy Enrique Bravo, Associate Human Rights Officer. “He is also an environmental defender and a defender of ancestral culture – it is not common to see such motivated young people and he deserves our recognition.”

Diego is now looking for financial support from local banks to advance his business and is getting help from his community. He has built a network of allies, ranging from childhood friends to former teachers to local artists, all joining in an informal Lenca network to help keep the culture alive.

“

This isn’t about individual growth, it is about growing together with his community.

“

Eloy Enrique Bravo, Associate Human Rights Officer with UN Human Rights Honduras

“He doesn’t want to save the Lenca culture by himself – he wants everyone to join him in doing it. Diego has a broad vision that entails supporting others so that change happens for everyone, with everyone’s voice being heard, not just his,” said Eloy Bravo.

Diego hopes to someday turn his mother’s street into a cultural corridor, filled with cafés, art galleries and shops, a true Lenca showcase for the world.

Fighting for the future

While he works to build his vision, Diego earns a living teaching art and inspiring his students.

“I want to motivate young people, help them use art for good rather than turn to crime or emigrate. Perhaps it can give them a reason to stay, and a way out of violence.”

“With my art and social messaging, I can help transform a street plagued by vandalism and crime into a safer space, turn something negative into positive.” Showcasing Lenca art would also gradually help bring in tourists.

Miriam Suyapa Lorenzo, indigenous leader of the Simpinula La Paz community and of the Local Human Rights Accompaniment Committee. © OHCHR Honduras

Joel Antonio Nicolas, indigenous leader of the community of Simpinula, department of La Paz and of the Local Committee for Human Rights Accompaniment. © OHCHR Honduras

Victor Vasquez, member of the Lenca indigenous community and human rights defender. © OHCHR Honduras

But Diego continues to be exposed to danger: some 70% of attacks against human rights defenders are against those working to protect the environment. Being an environmental activist or a human rights defender in Honduras comes with high risks – and Diego is both.

Once in a while, Diego still hears the call of the North, especially when he faces hurdles to get what he wants. But he quickly silences it.

“I’m happy I decided to stay, serving my community. I feel I can inspire others. I see the situation of other young people and I know I am not unique.”

Note: UN Human Rights hopes to build on this experience and empower young leaders across the country. A new project supported by the UN Peacebuilding Fund, Tierra Joven, aims to promote the meaningful participation of young women and men in decisions that affect their rights and access to land and territories.