Data mapping drives water revolution for Serbian Roma community

25 January 2024

Hundreds of Roma living in informal settlements in Serbia now have safe drinking water as a result of the country’s first comprehensive data mapping exercise.

This groundbreaking initiative, spearheaded by UN Human Rights at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, uncovered staggering realities: more than 30,000 Roma had little or no access to drinking water, over half lived without sewage services, and some 24,000 had limited or no electricity. Representing nearly 2% of Serbia’s population, the Roma community also grapples with high unemployment, poverty and discrimination, often exacerbated by underreporting due to the stigma attached to their identity.

Despite its 100-year-old history, the village of Gornja Grabovic in southwestern Serbia has never known the luxury of safe drinking water. “We had a well, but its water was unfit for drinking. On Fridays we collected water in bottles and cans from the market in the city, but in winter, traveling to the city was a formidable task,” said Danijela Marković, a lifelong village resident. The nearest city, Valjevo, is 6km away.

Ms. Danijela Marković is washing the dishes at her sink in her house. © Stefan Vidojević /MaxNova Creative

The start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 aggravated their situation, severing what little access they had to water and heightening the risk of disease.

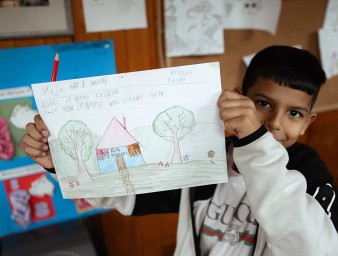

Children were particularly hard hit.

“They faced immense challenges. After sunset, their world turned dark, hindering their ability to work or play or study. The safety of these children, particularly girls, became a concern and often restricted their school attendance,” said Aleksandra Petrović of the UN Human Rights Office in Serbia.

The mapping work would reveal the plight of Gornja Grabovica’s residents and bring them much-needed help.

The pandemic as catalyst

Mr. Slavko Marković, a resident of the Gornja Grabobica village assists in the process of data collection. © Stefan Vidojević /MaxNova Creative

Lack of data on Roma communities has always made it difficult to provide assistance. A mapping effort had been planned for some time, but the pandemic and subsequent lockdown gave the work additional urgency.

“Almost immediately after the state of emergency was declared, our phones were inundated from morning to midnight with calls from all over Serbia desperately seeking assistance and providing information. Our goal was to leave no one behind, ensuring even the smallest and most remote Roma settlements were accounted for,” said Dragan Gračanin, a coordinator for Roma issues who was directly involved in the data collection effort.

The villagers of Gorna Grabovica and its surroundings did not have long to wait. Intervention was swift, providing water tanks, essential groceries and protective equipment to nearly 2000 families across 19 settlements.

In the end, the six-month mapping effort identified 167,975 inhabitants in 702 Roma settlements, and distributed 72,000 packages of essential food items, water, and protective gear to Roma households. All the data collected during the mapping would now be available for future planning.

Informing policy and programmes

This data-driven approach was pivotal: it helped identify those in dire need and formulate sustainable solutions. Its impact went far beyond immediate relief. By making communities more visible and highlighting their lack of infrastructure, the mapping would strengthen Serbia’s capacity to gather and use data for broader Roma human rights and development efforts.

“These data have been used in the Social Inclusion Strategy for Roma Men and Women, the Belgrade Roma Inclusion Strategy, and other important documents,” said Slava Denic, former manager of SIPRU, the government’s Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction Unit. The data were also used to update government databases, inform joint UN analyses, and underpin several donor-funded projects in support of Roma populations.

Aleksandra Petrović (UN Human Rights Team) and Dragan Gračanin (Coordinator for Roma Issues)- the process of data collection and double-checking. © Stefan Vidojević / MaxNova Creative

A key factor in the programme’s success was its collaborative approach. The mapping involved a range of partners, including UN Human Rights, SIPRU, and various donors. On the ground, an army of people took part in collecting data: 40 civil service organizations, 15 Roma United Nations Volunteers, and representatives from 94 municipalities. The information was meticulously verified, compiled and updated daily into a database managed by UN Human Rights and shared with partners.

“The role of UN Human Rights was crucial. Not only did it initiate the mapping, but it also created an inclusive environment and partnerships with all those involved,” said Aleksandra Kecojevic of the Ana and Vlade Divac Foundation, a Serbian humanitarian and development organization.

Hope, resilience, and the power of human rights data

The immediate results of the mapping were radical.

Andra Savčić primary school teaches 40 pupils in Gorjna Grabovica and for years, has been plagued by a water shortage. “We always had to bring water in large barrels for drinking and cooking, but the pandemic pushed the water issue to the forefront. The mapping helped highlight our immediate needs – and raised awareness about our village’s existence and its challenges,” said Danijela Janković, a teaching assistant at the school.

Now, the school boasts a steady water supply.

For Danijela Marković, the longtime resident of Gorjna Grabovica, life today is unrecognizable.

“My life has changed dramatically. We now have running water in our house, I can wash dishes at my sink. I no longer have to boil the well water or handwash clothes in the freezing cold. Fetching water from city taps is a thing of the past. We live like normal people now.”