Griselda Triana: Fighting for freedom of expression in Mexico

02 November 2023

When a journalist is assassinated in Mexico – almost once a month on average –people sometimes take to the streets. If that happens, Griselda Triana does her best to take part.

Her silver-streaked hair neatly swept up and her placard in hand, she adds her voice to the pressure. For years, human rights defenders have been calling on Mexican authorities to end the impunity that makes it easy for assassins to kill journalists and human rights defenders and get away with it. Sometimes, those same authorities may even be involved.

Griselda is both a human rights defender and a journalist… and the wife of the respected journalist, Javier Valdez. That she became a target should come as no surprise.

A day of tragedy

The month of May is hot in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa, so hot you’ll scour the street for the tiniest patch of shade.

Monday, 15 May 2017, was a scorcher.

The weekly editorial meeting had ended at RíoDoce, a local investigative newspaper known for raising social issues not to everyone’s liking.

After extracting the last strands of cool air from the stairwell, Javier Arturo Valdez Cárdenas stepped outside and walked towards his car, his trademark straw hat shielding his face from the sun.

A neighbour was the first to hear the shots, a dozen or so. By the time his colleagues rushed around the corner, Javier’s bleeding body was slumped on the street.

It would later be ascertained that two men had pulled him out of his car, a third driving off with the vehicle, abandoning it down the road.

Demonstrations broke out in various states across the country. Javier had been one of RíoDoce’s star columnists and founder, an indefatigable chronicler of corruption and cartels, and a source of information for international media, his reputation reaching across Mexico and beyond.

His death attracted a cascade of national and international interview requests and posthumous awards but throughout it all, Griselda remained silent.

“I locked myself up for months,” she said. “I avoided all the marches, the interviews. The assassins had vanished, and I was scared for my family.”

Her children were thrust into the spotlight.

“I finally had to react. We agreed the children would step back and that I would become the face of the protest.”

It is a mantle she would wear with pride.

Keeping memory alive

When Javier died, Griselda lost more than a husband: she lost a partner and team-mate. From the moment they began their careers, the journalistic duo had been inseparable, first on newspapers and later in broadcasting. She understood the risks of being an outspoken critic.

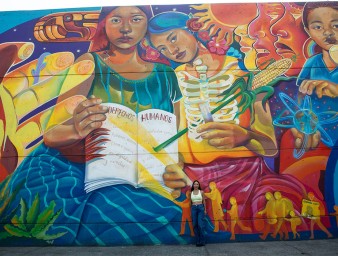

© Still of mural featuring Javier Valdez that reads “Nobody forgets here. Javier Valdez lives”, in Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico.

“During the late 1980s and the 1990s there was much violence in Sinaloa,” she recalls, “but we were not afraid. We were reporting morning and night, chasing ambulances and patrol cars. Often, we knew more than the police and arrived at the scene before them.

“We both loved journalism, the adrenaline, of course, but also the different perspectives, the going out and talking to people every day.”

Javier’s beat covered organized crime so when drug violence intensified in Sinaloa in the early 2000s, Griselda recognized his need to report the truth and refused to hold him back.

“I was scared but I would not voice it,” she said.

Barely two months before his murder, in the northern state of Chihuahua, veteran journalist Miroslava Breach Velducea was driving her son to school when a drive-by assassin pumped multiple bullets into her head. Like Javier, Miroslava often wrote about social issues – corruption, human rights, indigenous people – and about the growing drug cartel violence in her state. Her murder would help fuel Javier’s own outrage.

For years, journalists in Mexico – especially regional journalists without the support of major media employers – have been assassinated with impunity. Underpaid and overstretched, they usually work solo, often online or on social media only, without a safety net to protect them if they are victims of threats, attacks, or murder. Yet they consistently demonstrate courage and determination, pushing for truth in the face of enormous risks and extraordinary challenges, digging into stories that national media don’t know about or would prefer not to touch.

Javier was one of the exceptions, a regional journalist with a reliable newspaper to back his work. But this notoriety would fail to save him: Mexico is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists.

“The number of journalist assassinations in the country keeps going up,” said Balbina Flores Martinez, the Reporters Without Borders representative in Mexico. “Waves of violence lead to impunity in 90% of journalist assassinations.”

© Still of Balbina Flores, Representative in Mexico of Journalists Without Borders.

Of the three assassins who killed Javier, two were caught and sentenced, a third was found murdered before he could be tried, but the mastermind has yet to be punished. He is now in the United States with a request for extradition while serving time on an unrelated charge in a US jail.

“The system is imperfect, but this is one of the first cases in Mexico that is actually moving towards some resolution,” said Edison Lanza, Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights at the time of Javier’s death.

A watchful eye

As soon as news of Javier’s assassination became public, UN Human Rights reacted immediately, condemning the murder, and calling for an end to the cycle of attacks on journalists.

“Internationally, Mexico is a model human rights citizen,” said Jesús Peña, Deputy Representative of the UN Human Rights office in Mexico. “It has signed most human rights treaties and it pays attention to international recommendations.”

However, real access to justice in Mexico has proven to be far from the international image the country has modelled. Proof of that is the high rate of impunity regarding crimes against journalists.

As the investigation into Javier’s murder unfolded, the UN Human Rights Mexico kept up its pressure, deploring the lack of progress, meeting with prosecutors and other officials, and making sure the case did not backslide into “old news”. Later, the Office would attend the judicial hearings and observe how the first perpetrator was convicted.

For Griselda, that support was crucial.

“The interventions of UN Human Rights were pivotal,” she said. “They were a strong ally and accompanied us from the beginning, observing the government, keeping freedoms visible, and supporting our family in various ways right after the assassination.”

One thing Griselda understood from the start was that her position was unique.

“I had plenty of support from organizations like UN Human Rights and the lawyers at Propuesta Cívica,” Griselda said, “but I also realized many families did not. They had few resources and had to rely on the government to investigate. These families became fractured and isolated, the women suddenly become heads of family, and they have the right to reparations to help support them.”

“I almost felt guilty receiving all this special treatment – it should be the same for all families. So I decided to try to change that.”

After Javier’s assassination, life in Culiacán had become even more dangerous for Griselda and her family, and they scattered to different towns.

Conscious of the danger of cartel retribution, Griselda finally applied to Mexico’s protection mechanism for journalists and human rights defenders, which, depending on circumstances, may provide those under threat with a secret place to live, protection devices, and in the direst cases, daily police check or bodyguards. The system is not fool proof, however, and UN Human Rights has called on the government to reinforce it.

While Griselda is grateful for the protection, she cannot live like this forever.

“I’m counting the days until I can return home,” she said, but that date has still not been set.

Griselda’s battle

Today, Griselda continues to be an active human rights defender and a member of Sinaloa’s Consultative Council of the Institute for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. Her reach, however, goes far beyond the state.

She regularly sits on the jury of the nationwide Breach-Valdez Prize for Journalism and Human Rights, established jointly by UN Human Rights and several partners.

“Not every journalist has the possibility of publishing their stories in major media or writing books, but just the same they need to be recognized and rewarded. The prize does that. Now at least we can acknowledge the difficulties they face as journalists in Mexico.”

She travels internationally to speak about freedom of the press, calling for an end to impunity for assassins and keeping Javier’s memory alive.

Along the coast of Sinaloa, on the sandy beaches of Mazatlán, sun-hungry tourists remain oblivious to the cartels operating in the state capital a couple of hours away.

They might even unknowingly drive past the offices of RíoDoce, whose editorial line still includes narco-trafficking, along with other controversial issues such as corruption and money laundering.

“We are careful,” said Ismael Bojórquez, the weekly newspaper´s co-founder, “but assassination is always a possibility.”

This is the possibility Griselda wants to end.

“It is clear that in Mexico, those who kill journalists are not being punished,” she said. Her focus is now on the United States, which she hopes will extradite her husband’s murderer so he can be tried in Mexico.

By continuing to speak out, she amplifies the voices of those journalists whose own voices remain unheard.

None of this will bring back Javier, or Miroslava, or any of the dozens of journalists murdered since then, but it could help prevent future crimes. Shining a light on impunity may make it more difficult for assassins who, until now, have found it far too easy to muzzle journalists by killing them.

Partners in the Breach-Valdez Prize for Journalism in Human Rights include the United Nations Information Center in Mexico (UNIC); Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico (OHCHR – UN Human Rights); United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC); United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); Embassy of France in Mexico; Embassy of Switzerland in Mexico; the Press and Democracy Programme of the Universidad Iberoamericana (Programa Prensa y Democracia) and its Journalism Department; Agence France-Presse (AFP); and Reporteros Sin Fronteras (Reporters Without Borders – RFS).