Enforced Disappearances: “These wounds do not heal”

27 March 2023

“It is difficult to talk about my brothers,” said Heo Gum Ja, 62, who lost her two brothers to an abduction in 1975 by the Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK) while they were fishing. “You’d think I could forget, but every time the incident is mentioned, tears well up and my heart aches. We watched our parents suffer, so our hearts break when we think of them.”

Heo’s story and other personal testimonies from victims are featured in a new UN Human Rights report on the crime of enforced disappearances and related violations by the DPRK. It examines systematic abductions and enforced disappearances carried out over several decades, as well as the ongoing suffering of its victims, including relatives of forcibly disappeared persons.

“The anguish, sorrow and reprisals that families – across multiple generations – have had to endure are heart-breaking,” said UN Human Rights Chief Volker Türk. “The testimonies from this report demonstrate that entire generations of families have lived with the grief of not knowing the fate of spouses, parents, children and siblings.”

The UN Commission of Inquiry on the situation of human rights in the DPRK (COI) reported in 2014 that State-sponsored abductions and enforced disappearances of people from other nations were unique in their intensity, scale, and nature in the DPRK. The COI concluded that enforced disappearance on a large scale as a matter of state policy constituted a crime against humanity.

UN Human Rights conducted interviews between 2016 and 2022 with 38 men and 42 women who are victims of enforced disappearances, including people who escaped the DPRK and relatives of the forcibly disappeared

The enforced disappearances and abductions addressed in the report follow two patterns. The first pattern involves the ongoing practice of arbitrary arrest and detention of DPRK nationals, including those accused of political crimes and those who attempted to leave the country and were forcibly repatriated.

Families are often not notified of their relatives’ detention, and authorities have refused to disclose the reasons for the detention and the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared persons. The report also noted that in the DPRK, family members searching for a disappeared person can be at risk of intimidation, reprisals, and disappearances due to their association with the disappeared person.

A second pattern includes the enforced disappearance of foreign nationals outside the country, mainly between 1950 and the mid-1980s, but continuing until 2016. These included abductions of nationals of the Republic of Korea during and after the Korean War, non-repatriation of prisoners of war (POWs), and abductions of foreign nationals from Japan and other countries.

Hardship & Pain

In the Republic of Korea, the DPRK armed forces abducted and forcibly relocated civilians living in the Republic of Korea to the north during the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. It is estimated that around 100,000 people were abducted, most of whom were men forcibly taken from their homes for their skills, expertise or labour that could be useful for the DPRK Government.

Choi Kwang-Seok, 89, still remembers the precise moment he last saw his father, Choi Jun. They were both detained by DPRK forces at the Dongdaemun Political Security Bureau in Seoul in 1950. Before he was released from detention, Choi knew that his father was tortured.

“I asked to see my father just once before I left, which was permitted,” he said. “He was utterly worn out and was leaning [against something] because there wasn’t enough space to lie down. I said, `Father, I’m going home,´ at which he suddenly said, `Goodbye.´”

“

I still wait for him and will continue waiting for him forever…I would like to know how my father has been all this time.

“

Choi Kwang-Seok, 89, son of Korean War abductee

At the end of the Korean War in 1953, tens of thousands of prisoners of war were held by the DPRK or its allies and only 8,343 were returned. The COI estimated that at least 50,000 POWs from the Republic of Korea had not been repatriated. POWs were reportedly forced to work in coal mines in the northern parts of the DPRK where they faced discrimination and surveillance. Their children were left without access to tertiary education and faced many other forms of discrimination.

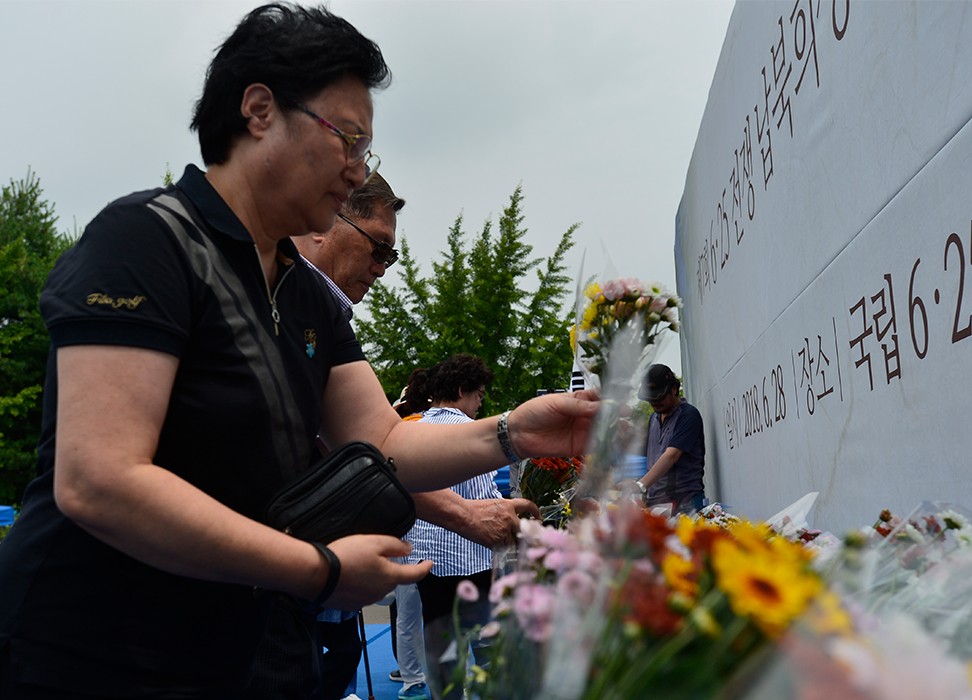

After the Korean War, 3,835 people were abducted by the DPRK, and 516 of these post-war abductees remain missing. Most post-war abductees were fishermen, but victims included police officers, soldiers, crew members and passengers of a hijacked Korean Airlines aircraft, and high school students.

“My life was completely turned over after my father was abducted,” said Kim Jong Hui, 59, daughter of a post-war abductee. “Our household was ruined, it was hard to come to my senses, and my life was turned upside down.”

Among the enforced disappearances carried out by the DPRK in other countries, the largest group of abductees are nationals of Japan. The Government of Japan has officially identified 17 Japanese nationals as abducted by the DPRK and is investigating 871 cases of missing persons where the possibility of abduction by the DPRK can’t be ruled out.

Japanese national Iizuka Shigeo’s sister was abducted in 1978. He sought information about her for decades.

“I really want to know the whereabouts of her and also whether she is healthy or she is sick,” he said. “I really want to see her photos. I really wish to have her photo.”

Iizuka passed away in 2021 without ever knowing what happened to his sister.

About 100,000 ethnic Koreans were lured to move to the DPRK from Japan based on false promises of a better life, known as the “Paradise on Earth” campaign, according to the report. After their arrival, they were subjected to surveillance and censorship, and they were never allowed to return to Japan. The COI concluded that these people may have potentially become victims of enforced disappearances.

The report also examines how enforced disappearances have caused serious mental and physical harm to victims. The impact was especially severe when a family’s father or husband was taken away, as women had to shoulder the entire burden of supporting their families.

“These deeply tragic stories of lives ripped apart by State-sponsored abductions and enforced disappearances demand action,” said UN Human Rights Chief Volker Türk. "Enforced disappearance is a profound violation of many rights at once, and responsibility lies with the State.”

“

I call on the DPRK to acknowledge these violations and take steps to resolve the cases, and on all States to support victims of enforced disappearance in their quest for justice.

“

Volker Türk, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

The Office will continue to monitor and support victims by exploring strategies for truth and justice, including accountability and reparations. The families informed the Office what they want most is simply to know the truth about the fate of their loved ones. They also want the immediate and safe return of the disappeared, the return of the remains of those who have died, and reunification of families with those who are still alive.

“Since many people have family and relatives left behind in the DPRK, I believe the utmost priority would be to confirm the fate of those people,” said Ishikawa Manabu, 64, a victim of the “Paradise on Earth” campaign. “I also believe these issues will naturally be solved when people are free to come and go.”