Justice delayed but not denied: transitional justice in El Salvador

02 April 2020

It has been nearly 40 years since Dorila Márquez survived the horrific attack that left hundreds dead, including her brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews.

“It was purely a miracle I survived,” she said. Márquez and a few others had hidden in her home when the soldiers came. It was by some miracle that the group of soldiers divided in front of her home, one group going one side, one to the other, ignoring her house. Over the course of the day, Márquez heard the screams, the gunshots the explosions. It wasn’t until she exited her home the next day that she saw the scale of the violence – burnt out homes, burnt fields, dead livestock, and so many burnt bodies.

“We smelled the burnt body smell all day.” She paused to take a shuddering breath. “El Mozote was flooded with black smoke and bullets.”

Over the course of three days in December 1981, soldiers who were part of the El Salvador Army murdered nearly 1,000 civilians in El Mozote and other towns in the northeastern part of the country. El Salvador’s civil war lasted just over 12 years, from 1980 to 1992.

However, survivors and families have spent years fighting for recognition, justice and reparations. Decades of denial of the massacre by former government, a new administration and bureaucratic mazes have left expected reparations stalled.

Into this bureaucratic puzzle stepped the UN Human Rights Regional Office for Central America (ROCA), which since 2016 has worked in El Salvador to provide technical assistance and support through the twists of transitional justice. The Office has provided technical and legal support to the country’s Attorney General’s Office and to civil society for the investigation and criminal prosecution of crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in the context of the armed conflict.

“It was only after the rejection in 2016 by the Supreme Court of the 1993 amnesty law that victims and family members could see the light to get some justice and dream of the truth hopefully being known” indicated Marlene Alejos, who was recently Regional Representative for Central America and Head of the UN Regional Office.

Overturning Amnesty

In 2016, El Salvador’s Supreme Court struck down an amnesty law approved in 1993. The law had made it impossible to prosecute those involved in massacres, such as what occurred in El Mozote, as well as other gross human rights violations and war crimes. Julio César Larrama, from the Attorney General’s Office, said this not only opened up the chance for prosecutions of military and non-state officials for war crimes, but it also showed the need to better training on handling such cases.

“We know perfectly well that these events occurred many years ago, but if you talk to a victim of a serious violation of human rights that occurred in the context of war [for those victims] it is as if those events occurred yesterday,” he said. “We do not want to cause double suffering, and that is why we asked the UN Human Rights Office to train us in this.”

Alejos said that one of the Office’s main contribution was the adoption at the end of 2018 by the Attorney General of the “Policy on Investigations and Criminal Prosecutions of Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes,” a policy document elaborated with the technical support of the Office after consultation with survivors, civil society and prosecutors. The policy contains an action plan and tool kit to assist the Attorney General’s Office in transitional justice cases.

Larrama, who is the coordinator for prosecutors working on the cases stemming from the armed conflict, said the UN Human Rights Office facilitated important information exchanges with counterparts from other countries in similar situations, such as Colombia and Guatemala. “They had a war much longer than ours, and have obtained very good results in the cases they have aired.”

This work has been welcomed by civil society. The Office meets on a monthly basis with 16 NGOs that are part of an advocacy to combat impunity. Sonia Rubio, an advocate and lawyer with Due Process of Law Foundation (DPLF), is from one of those NGOs. She said the transitional justice landscape looked bleak in El Salvador. Although the amnesty law was overturned, a new measure that would grant a level of impunity to for crimes against humanity from the civil war was making its way through the legislature.

“In El Salvador, I believe that it is necessary to mobilize not only human rights defenders, but other sections, both nationally and internationally and that is why we believe the support of the UN Human Rights Office can … bring the situation of transitional justice to light and generate a hope that can battle impunity,” Rubio said.

In February this year (2020), El Salvador President Nayib Bukele vetoed the bill that had been approved by lawmakers. He said he would not support any measure that did not contain three fundamental elements: truth, justice and reparations.

Live for justice

The back and forth over recognition, justice and reparations is becoming increasingly frustrating each passing year. Many survivors are in their 70s and 80s – fighting not just the government, but the clock.

Virgilio Cruz is 79 and from El Mozote. Although he was not in the village at the time of the massacre, he did lose family and friends. He said he has little trust in the judicial process and does not expect to live long enough to see any sort of justice for those who died.

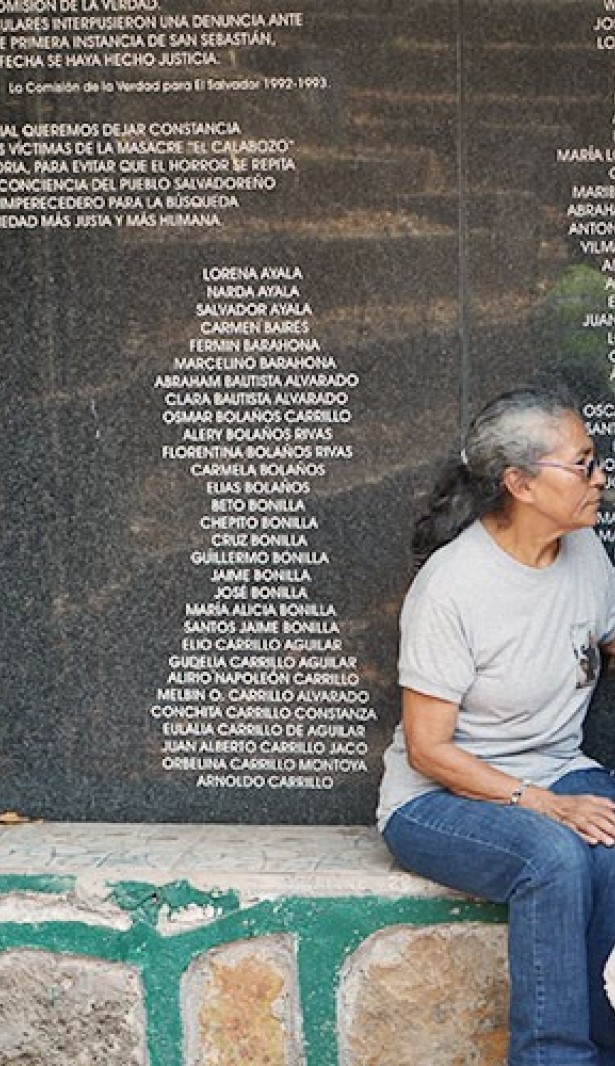

“I doubt very much that this a proper or transparent legal process,” he said, standing in front of the granite wall memorial to those who died in El Mozote 38 years ago. “I do not see it as positive.”

Miriam Abrego lives and fights to see justice. She was cooking soup in her home when soldiers came into her tiny village of San Francisco Angulo, called out to her, and shot her twice. She managed to survive, but 45 others were not as lucky. More than 30 years on, she advocates for those who survived like her and the families of those who died or are missing, pushing for their voices to be heard.

“We are in a pretty sad situation that we keep having to talk about this,” she said, standing before a memorial where the remains of those who died are interred. “[The government and others] keep telling us to shut up. But me, I won’t shut up. We victims are tired. We want to be recognized as victims. We want to be heard. There are people who are dying and still there is no justice. So tell this, to society, to the United Nations, to the world. We need support. Hear our pleas.”

2 April 2020