Migration nightmare for an indigenous woman in Mexico

10 August 2018

“Police officers asked me about my participation in the kidnapping of two migrant women and forced me to accept that I was part of group of polleros, even though I could not understand what that means,” recounted Juana Alonzo Santizo. “After 4 years in prison I learnt a bit of Spanish and only then could I understand what were the criminal charges against me,” she added.

Santizo, an indigenous Chuj woman from Guatemala, left her hometown in August 2014 in the hope of reaching the United Sates. A migrant smuggler, also known as a coyote or pollero, had already laid out a plan for her:she wouldcross the Mexican border with Guatemala and get to the northern Mexican city of Reynosa, in the state of Tamaulipas, near the United States border.

Along the way, Santizo, who could not communicate with others in her group because she did not speak Spanish, could not tell where she was. The coyote reassured her by saying they were close to entering the United States.

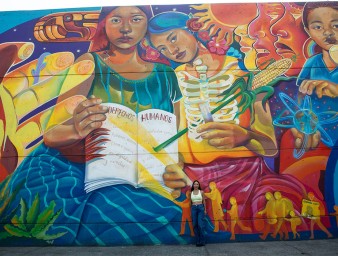

Every year, thousands of migrants from Central America cross the length of Mexico’s territory to flee from violence, disappearances, executions, torture, poverty and gang-forced recruitment. Many of them are asylum seekers and migrants in transit trying to reach the United States in search of better life opportunities.

Border checkpoints in Mexico have forced migrants to use more dangerous routes in an attempt to escape detection, detention, and deportation. Smugglers often kidnap and extort migrants during transit, and even abandon them on inhospitable routes.

When her group reached Reynosa, the coyote and other groups of unknown men sequestered Santizo with two other migrant women in a private house. There, the women were forced to work for their captors.

Eventually, one of the victims found a way to call and expose her kidnappers to the local police. While they were being rescued, the two women accused Santizo of being linked to the kidnappers, taking advantage of the fact that she could not understand their claims against her.

She was subsequently detained by the police officers and moved to the local police station in Reynosa. During her interrogation, Santizo once again faced the language barrier and could not reply to the questions asked. She claimed that, in retaliation, the officers beat her and threatened her at gunpoint. She eventually gave in and signed a self-incriminating declaration.

Santizo recalled that neither lawyer nor interpreter was present during the interrogation, nor did she receive medical attention. She also claims that during her public hearing before the judge, she was forced by the agent of the Public Prosecutor's Office to ratify her statement. In November 2014, she was transferred to a State prison in Reynosa.

According to Santizo, the authorities have never recorded nor investigated her claims of being tortured, neither did they question the self-incriminatory declaration she signed.

The UN Human Rights Office in Mexico visited Santizo in prison, and advocated for her rights and expressed concerns over her detention conditions with the director of the penitentiary. The Office has also interceded with the Guatemalan Consul to request her access to an interpreter and consular protection.

Further, UN Human Rights Mesxico has accompanied Santizo’s uncle to report the torture she endured to the Attorney General's Office in Reynosa and the Mexican Human Rights Commission.

In Guatemala, the UN Human Rights Office has garnered the support of the National Human Rights Institution, the Office of the Attorney General and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to guarantee Santizo’s human rights while detained in Mexico.

Now, Santizo’s family, who she was unable to contact until April 2018, is bearing the cost of an interpreter to travel from Guatemala to Mexico, to assist her for the first time in almost four year in making a new statement before the Judge.

August 9 is International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. On that day, a group of UN independent human rights experts urged States to ensure indigenous people’s rights under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, and to recognise these rights in the context of migration.

10 August 2018