Statements Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

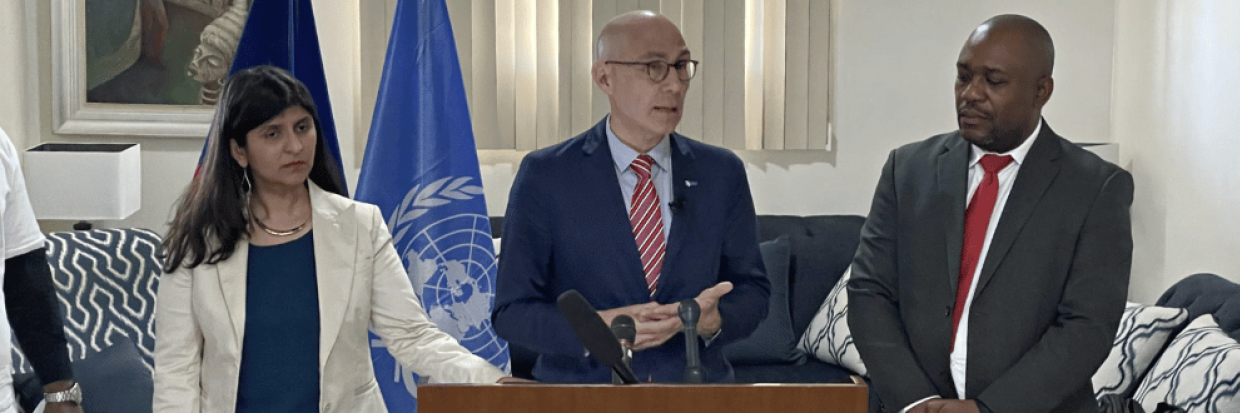

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk concludes his official visit to Haiti

10 February 2023

Location

Port au Prince

Mesye dam bonjou (Good morning all). Thank you for coming and let me begin by thanking the Government of Haiti for its invitation to visit, and for the frank discussions we have had over the past two days.

At a time when multiple crises around the world are competing for attention, I fear that the situation in Haiti is not receiving the urgent spotlight that it deserves. As the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, I am here to cast that spotlight and to help spur action for Haitians.

The world needs to hear what I have borne witness to and what my colleagues document every day from some of the poorest, most frightening situations in the world – a capital city where, in many areas, predatory armed gangs control access to water, food, healthcare and fuel, where kidnappings are rampant, children are prevented from going to school, recruited to perpetrate violence and subjected to it. A country where one out of every two people faces hunger, lives in extreme poverty and does not have regular access to clean drinking water. Where prisoners are dying of malnutrition, cholera and more. Let’s not forget the vulnerability of the country to natural disasters.

The issues are vast and overwhelming.

But I am also here to caution against writing off the situation in Haiti as insurmountable and hopeless. Haiti and Haitians must not be defined by the reductionist view of them as victims.

Many speak of a country that lurches from crisis to crisis. I see a people with a long history of resilience and grit in the face of a series of crises, from natural disasters to man-made ones imposed from the outside and from within. This is, after all, a country born out of the fight for dignity and human rights against colonialism, slavery, systemic racism and oppression.

I also sensed, however, the exhaustion that comes from shouldering these burdens day after day, and I heard a plea for help. An SOS cry from the much-beleaguered communities.

The way out of these multiple human rights crises must be owned and led by the people of Haiti, but the magnitude of the problems is such that they need the international community’s active attention and targeted support.

Today, I am issuing a report* by my Office that sets out the debilitating impact of gang violence in several parts of the Cité Soleil region of Port-au-Prince. In just one neighbourhood of Brooklyn – in the grip of gang violence – at least 263 people were killed, 285 injured and four disappeared between 8 July and 31 December 2022. We have documented rapes and gang rapes of women and girls, destruction and pillage of houses and displacement of people from their homes. Since July, gangs have been perpetrating a near permanent climate of terror, including by employing snipers to shoot at people indiscriminately. Movement of individuals is restricted and access to basic needs blocked, including water, food and sanitation services – creating an environment ripe for the spread of infectious diseases, including most recently, cholera.

With entire communities effectively held hostage by gangs, State social services are largely absent. While non-governmental organisations and UN agencies are working to provide much needed aid, so-called “foundations” in these neighbourhoods are often used by gangs to exert control.

These gangs possess a range of weapons and sow fear and violence into the communities they control. Sources have informed us that members of the gangs distributed machetes to relatives of people killed by a rival gang coalition calling on them to take revenge.

It is estimated that some 200 gangs operate around Haiti, in the capital but also spreading in the centre and northern regions of the country, such as the Artibonite and North departments. More than 500,000 children living in gang-controlled neighbourhoods are struggling to access education. Many have suffered grave violence.

I met a 12-year-old girl who survived being shot in the head by gang members. And another young girl who had been gang raped. Such depraved violence against the children, women and men of Haiti is met largely with impunity.

State authorities have not been able to respond adequately and at least 18 police officers have been killed since the beginning of this year due to gang violence.

The lack of resources and personnel in the police force, coupled with chronic corruption and a weak judicial system mean that impunity has been a core problem for decades now.

This must not continue.

In my discussion with senior officials, civil society, my UN colleagues and the international community here in Haiti, I have emphasized that measures to re-establish security will need to focus on accountability, prevention and protection to be successful and sustainable. There is an urgent need to strengthen the criminal justice system, improve the penitentiary system – notably with 80 percent of the prison population in pre-trial detention – and to address corruption and impunity.

Rampant corruption is a barrier to the realization of economic, social rights, further undermines already fragile institutions, including the judiciary and the police, and is deeply corrosive in every aspect of the daily lives of the Haitian people.

The prevailing security crisis has of course deepened the economic plight of Haitians. More than half of the 11.8 million people in Haiti live below the poverty line. In October last year, year-on-year inflation reached 47.2 percent. Some 4.7 million people are acutely food-insecure and a shocking 19,200 people are estimated to be in a catastrophic situation, living in famine-like conditions. In 2022, it is estimated that only one in two people (48%) had regular access to clean drinking water. The situation in prisons is particularly precarious, with ever-worsening shortages of food, medication and water.

Gang violence has displaced large numbers of people. As of November, there are 155,139 internally displaced people across the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince. About a quarter of these displaced people live in spontaneous sites, most without access to basic services such as treated water, adequate hygiene and sanitation. The other 75 percent live within host communities, sharing already scarce resources. It is urgent for the authorities to respond to their particular situation.

In my discussions with civil society, the plight of vulnerable communities came out strongly, including women, LGBTI people, people with disabilities, young people and children. And what also came across strongly is the need for civil society organisations – and for that matter, every actor who can help shape events in the country – to play an active and constructive role in the political dialogue process and other platforms to identify solutions – small-scale and large-scale, short-, medium-, and long-term.

The situation in Haiti is desperate. But there is a wellspring of potential to turn the corner. To unleash the potential for profound change, political and economic elites must overcome their indifference to the suffering of the majority. They must ensure that it is the Haitian people who wield the power. I have called on the authorities to pursue an inclusive dialogue, building on the 21 December national consensus agreement, to find lasting solutions to the multidimensional crisis that Haiti is undergoing, particularly through the organization of prompt, free and transparent elections for the restoration of democratic institutions.

I have also urged the international community to ensure that Haiti features high on its agenda. The Haitian National Police needs immediate coordinated international support commensurate to the challenges to strengthen its capacity to respond to the security situation in a manner consistent with its human rights obligations. I also call on the international community to urgently consider the deployment of a time-bound specialized support force under conditions that conform with international human rights laws and norms, with a comprehensive and precise action plan. This must be accompanied by rapid and sustainable re-establishment of State institutions in gang-free zones, as well as a profound reform of the judicial and penitentiary system. The sanctions regime is an important first step. It needs to be accompanied by bringing perpetrators to justice in Haiti.

Equally important is strengthened international cooperation for increased border controls to stop the illicit arms trade and trafficking.

Given the history of international involvement in Haiti, there are lots of lessons to be learned. International involvement needs to be approached with humility, with the consistent, active participation of the people of Haiti and with a constant eye on the most vulnerable.

And until the dire situation in the country is resolved, it is clear that the systematic violations and abuses of human rights do not currently allow for the safe, dignified and sustainable return of Haitians to Haiti.

Even so, 176,777 Haitian migrants were repatriated last year. In my visit to the Ouanaminthe in the northeast of the country, I heard terrible stories of the humiliating treatment to which many migrants are subjected to, including pregnant women and unaccompanied or separated children.

Let me stress this again: international human rights law prohibits refoulement and collective expulsions without an individual assessment of all protection needs prior to return.

I leave Haiti shortly, but of course the important work of the human rights team within the UN presence here will continue. I welcome the openness of the Government of Haiti to strengthening the UN human rights presence in the country. There is much scope for us to support the Haitian people and work alongside them to strengthen their institutions, help strengthen civic space, to continue to monitor and report on human rights violations and abuses, encourage survivor-centred approaches to combatting sexual violence, support to judicial authorities and Haitian National Police and more. I commit to reinforce my Office’s support to confront these challenges.

A profound transformation is needed in Haiti and human rights need to be at the centre of envisioning a better future for all. I am hopeful that with the active involvement and wisdom of its people, coupled with international support and assistance, Haitians can bring out the incredible richness of this country. Despite all the problems, progress is possible. On our part, we pledge to stand with the Haitians who are taking great risks, every day, to protect human rights in the most trying of circumstances.

Mysion mwen an fini men travay la ap kontinye. Mèsi anpil. (My mission ends but the work continues. Thank you very much.)

*To read the full report, please click here

For more information and media requests, please contact:

Ravina Shamdasani – ( travelling with the High Commissioner) ravina.shamdasani@un.org

In Haiti

Beatrice Nibogora - + 509 36537043 /nibogorab@un.org

In Geneva

Jeremy Laurence - +41 22 917 9383 / jeremy.laurence@un.org or

Marta Hurtado - + 41 22 917 9466 / marta.hurtadogomez@un.org

In Nairobi

Seif Magango - +254 788 343 897 / seif.magango@un.org

Audiovisual

Anthony Headley – +41 79 444 4557 / anthony.headley@un.org

Tag and share

Twitter @UNHumanRights

Facebook unitednationshumanrights

Instagram @unitednationshumanrights