Profiles from African Countries

A Shield for People Caught Between Both Sides of War

Collective against Impunity and the Stigmatization of Communities (Burkina Faso)

Daouda Diallo (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by CISC)

The first sign of a resurgence of violence in the Sahel came in 2015 when Burkina Faso faced mounting violence from jihadist organizations, especially the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (EIGS). In response, self-defense groups named “Koglweogo,” formed in many rural communities.

In turn — while wrestling for control of the country — these groups also began committing unlawful killings and torture in the name of community policing. Soon after, in 2016, experts from the UN Committee against Torture expressed their concern about the grave attacks on human rights attributable to members of self-defence groups.

Through it all, including a 2022 coup that removed President Roch Marc Kaboré from office and dissolved the government, there is one man who documented and spoke out about the atrocities committed by both the rebels and the army: Daouda Diallo.

Diallo is a pharmacist and human-rights advocate who formed the Collective against Impunity and the Stigmatization of Communities (CISC) to document abuses endured by his fellow citizens. Founded in January 2019, when the Koglweogo groups attacked several villages and massacred mainly Fulani men, CISC makes up 30 or so civil society and humanitarian organizations.

“Burkina is a failed state because the country is under attack, threatened and powerless in the face of attacks by armed terrorist groups and growing banditry,” Diallo told PassBlue, an independent newspaper that covers the United Nations. “Burkina Faso is (also) a country where private justice has become more powerful because Burkinabè citizens no longer turn to the courts to solve their problems but take justice into their own hands.”

A Country-Wide Safeguard

Organized at the national level, CISC has representatives in each region of Burkina Faso, as well as focal points in the provinces and different communes to spot cases of torture or human rights violations as they occur. These sentries then use communication channels such as WhatsApp and Signal to send information back to CISC so that the organization can mobilize resources to act.

Following an alert from their focal points, CISC mobilizes to find victims of enforced disappearance, pass on information to victims’ families, and contact governors, prosecutors and others to take legal action. With assistance through the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture, the services of the CISC are free and accessible to all survivors and their families.

Lately, the services provided by CISC — listening, documenting and finding resources for victims — have sought justice from militias who rounded up people and held them for committing "suspected acts of terrorism.” On 11 May 2020, 12 of the 25 people who were arrested and tortured by the gendarmerie died in prison..

But Diallo has hope that the situation will change, staking a normal life — not hiding from death threats, living among his peers and with his family — on it. “I would simply tell (our new president) that the Burkinabè expect a lot from him and that he cannot make mistakes,” Diallo said. “The president of the MPSR must act urgently to make each citizen understand that in a nation, the negation of the other has no place. He must also act urgently for the protection of human rights because the tree of peace is watered with… justice.”

In his struggle to defend human rights, Diallo was elected winner of the 2022 Martin Ennals Award, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for Human Rights. Following this international recognition, he was welcomed and decorated by the new authorities of his country. With humility, he considers that these recognitions challenge him to pursue more commitment and more determination in the pursuit of human rights.

The Collective against Impunity and the Stigmatization of Communities (CISC) received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2022.

Keeping the Peace in a Young Sudan

Dialogue and Research Initiative (South Sudan)

Sarah, Michael (survivors) escorted by a DRI officer

‘Blue House’ is the name given to the notorious detention facility run by South Sudan’s National Security Service (NSS). Based in Juba, it is estimated to hold between one and two hundred detainees at any given time.

Information deemed credible by a UN Commission identified 21 men, labeled as dissidents, who were murdered by security personnel while in custody at Blue House, or a similar Juba-based facility, between 2016 and 2019. Having been detained arbitrarily, they also were tortured prior to their deaths. Often, this torture was sexual in nature.

The civil war has led to gruesome violations from both sides. According to Yasmin Sooka, the Chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, much of the past decade has been marked by brutally violent conflict and on-going human rights violations. As is often the case in conflict, women bear the brunt of the abuse. Sooka says sexual and gender-based violence in South Sudan is extraordinarily high. For South Sudanese women and girls, rape, torture, sexual slavery, forced marriage and abductions have become the norm.

One such victim, an elderly woman, told the UN Commission: “I am tired of all the abuse. I am old and no longer ashamed. I am just fed up.”

Gordon Lam, executive director of the Dialogue and Research Institute (DRI), a transitional justice, human rights organization that assists victims, says the government’s current transitional period is proving ‘challenging’. “We must make sure that our government is changed from the mentality of guerrilla to a modern governance system,” said Lam.

Seeking Justice

With funding from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture, DRI has created a networking mechanism for survivors of torture to demand justice and accountability from South Sudanese leaders. One of those survivors is Nyameada Gatjuat, who was abducted by armed groups in 2016 at age 15, after her father was tortured and killed by armed groups in Bentiu. Now, she is leading the search for justice and accountability for her father.

On multiple occasions throughout the years, UN experts have voiced their concern about widespread impunity in the country.

“I was down for 4 months due to fear of reporting the abuses, including when I was raped while searching for firewood,” Gatjuat said. “Through the DRI outreach team, I was made aware of possibilities of seeking true justice despite the long ground impunity in South Sudan'', she said.

“The funding has created a strong networking for victims and survivors of torture to call for justice and accountability in South Sudan,” Lam said. DRI is reaching out to the families of victims of tortures, gang rapes and kidnapping. Lam said governance is the bottom line that will create unity among the citizens. “Because when you have good government there will be no feeling of tribalism” he said.

The Dialogue and Research Initiative received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2021.

Helping Men Survive Sexual Assault Torture

Refugee Law Project (Uganda)

Aimé Moninga (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by Refugee Law Project)

The room in the corner of the Refugee Law Project’s main building was lined with low wooden benches and an assortment of plastic and metal chairs — every spot taken, as a heavy tropical heat bore down on each person.

Aimé Moninga, the group’s founder and organizer, offered everyone gathered a warm welcome, followed by an invitation for each person to briefly introduce himself. Men of every age, most shapes, and a variety of ethnic signatures from English and French to Swahili spoke to say their names and how long they had been a member of Men of Hope. The majority of them were undernourished and many were recovering from painful surgeries and medical interventions.

Moninga, a survivor of sexual abuse during the decades-long conflict in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo, then cited a preamble: “We call ourselves Men of Hope, because together we are building a future that is hopeful. A future in which we… now better understand that men are targeted for rape and all forms of sexual violence in conflict-related situations, and that when male survivors have access to medical care and psychosocial support the quality of life for each man and his family is significantly raised.” The rest of the men repeated, “You are not alone."

Standing Up for the Previously Neglected

Male survivors face an uphill battle for resources and recourse when they are sexually assaulted, as the majority of international attention and funding surrounding sexual violence focuses on female victims.

“Many men die in silence because … they feel that they don’t deserve to be called men again,” Moninga said. “I have experienced loneliness, shame and personal crisis after being sexually abused like an animal. For a long time I was tortured by my own thoughts. Through the Men of Hope organization, I realized I wasn’t the only one.”

With financial support from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture,Uganda’s Refugee Law Project formed Men of Hope in 2011 after seeing a number of male survivors of sexual torture from around the Great Lakes region come into its office seeking legal redress. It brought together three male survivors to begin a discussion about their specific experiences and challenges. Within a year, the number of men participating in this small group had increased to more than 40, meeting at least once a month.

Members of Men of Hope have been able to develop resilience and mutual support through collective action. They visit one another in hospital, make contributions to one another in financial emergencies, provide their skills, such as nursing, to members of their family when needed and engage in peer counseling. They also began to identify other survivors in the community and invite them to join.

The Refugee Law Project received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2003.

Relief After the Brutality of the Arab Spring

Organisation Mondiale Contre la Torture (Tunisia)

Jamel (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by OMCT)

When Jamel, a young Tunisian father of two toddlers, arrived at the scene of a fistfight in 2016, he expected local police to help him pull his brother out of harm’s way. Instead, they beat him until he was unconscious.

In January 2011, Tunisia became the first country in the Middle East and North Africa region to change its autocratic regime through a widespread and peaceful popular uprising. After the revolution, laws, and prevention mechanisms evolved gradually. However, the UN Committee against Torture expressed concern about the persistence of law enforcement violence, torture, and ill-treatment. Further, in recent years, impunity has increased and encouraged the continuation of these practices, according to the UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture.

Jamel remained in a coma for more than four months, leaving his family destitute. Being the breadwinner of the family, Jamel’s absence put the entire family in a difficult situation. The Organisation Mondiale Contre la Torture (OMCT), an international NGO with a direct assistance program in Tunisia called SANAD, helped find Jamel’s wife a job so that his family could survive. As part of its SANAD programme, the OMCT provides access to holistic assistance for Tunisian torture victims. When doctors diagnosed Jamel with paralysis, SANAD paid for his physical rehabilitation and surgery in a private clinic. SANAD also facilitated a living allowance from Tunisian social services for Jamel, who remains without a job due to his disability.

“I don't want to imagine my life and that of my family without the support of SANAD. They were the only ones who supported me when everyone else let me down,” said Jamel.

Providing Crucial Help for Torture Victims

Since the opening of its office in Tunisia in 2011, the OMCT has supported civil society organizations and public authorities in the country by strengthening their capacities in the fight against torture and supporting those submitted to the practice. The care it offers is multidisciplinary, of high quality, and coordinated with the victims and their families. The OMCT work under SANAD is supported by the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture.

“Within SANAD, we work every day to support our beneficiaries towards autonomy and the reconstruction of their lives,” said Najla Talbi, the Director of SANAD. “The stories of 700 direct and indirect victims that we have been able to assist since 2013 mark us day by day and confirm that our presence for them is crucial.”

Even after Jamel’s life was resettled, his mother never gave up on justice. Although the families of Jamel’s assailants tried to convince her to drop the charges by offering 40,000 dinars, she sought a lawyer through SANAD. Eventually, the police officers who beat Jamel were arrested and detained for more than a year before they were released. The case is pending at the court of appeal.

“Unfortunately, other victims — intimidated, desperate or uninformed — do not come to the three centers, and do not have the opportunity to tell their ordeal or to benefit from the necessary assistance and support,” Talbi said.

OMCT Tunisia received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2017.

Fighting the Stigma of Albinism

Standing Voice (Malawi)

Bonface Massah (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by Standing Voice)

In June 2017, Emily Kuliunde was found in Dowa, Malawi, after her family and neighbors chased and caught her attempted kidnappers. She lived to tell the tale. Just one week later, Mercy Zainabu Banda — another woman with albinism — was killed in Lilongwe. Her attackers had taken her hand, right breast, and hair.

To Bonface Massah, the Malawi country director of Standing Voice, an international NGO that assists people with albinism, a condition that causes a lack of melanin pigment in the skin, neither the abduction nor the murder came as a surprise. Malawi belongs to a group of about two-dozen African nations in which people with albinism face extreme discrimination and danger. They are at risk of being killed either for their body parts, which many believe to have magic powers, or simply because they are different.

In this context, and with financial support from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture, the organization provides specialist care and rehabilitation to people with albinism who have been affected by torture, and their families. It established first-response teams who handle incidents of violence in Tanzania and Malawi, providing a complex package of tailored material support that can include: psychosocial counseling; housing and home security measures; micro-finance and livelihood support; medical or school supplies; strengthening of access to services including healthcare and education; facilitation of trauma recovery or family reconciliation; and direct advocacy interventions in situations of risk, conflict or exclusion.

Discouraging Witchcraft and Superstition

“Despite important progress in recent years, people with albinism continue to experience discrimination and violence across Africa,” Massah said. “I have been horrified by the recent resurgence of attacks against my brothers and sisters with albinism.” Massah cites a range of recent atrocities against people with albinism in Malawi, including a string of murders, mutilations, abductions, and grave desecrations over the last 18 months.

Malawi's government has tried various means to end these attacks. In 2019, it even distributed mobile security alarms to people living with albinism. But Massah called such measures a “very good, clear indicator of a failed system,” echoing the UN stance that albino kidnapping amounts to torture.

A 2021 UN Human Rights report stated that attacks against persons with albinism are “manifestations of the worst forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and can never be justified” and “qualify as torture, both physical and mental, if the authorities fail to provide the necessary preventive and protective measures,”

Standing Voice reports that, as of June 2022, 220 people with albinism have been murdered, and 780 attacked, across 29 African countries since 2006. Those who have survived sometimes have deep physical scars and psychological trauma, fearful their tormentors will return.

“We implore affected countries to take accountability for the welfare of their citizens with albinism”, Massah said.

Standing Voice received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2020.

An African Refuge

Bienvenu Shelter (South Africa)

Ex-resident, now a staff member (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by Bienvenue Shelter)

When the Apartheid regime officially ended in South Africa in 1990, the flow of migrants from other African countries increased tenfold.

To fill a gap in government services, the Congregation of the Missionary Sisters of St. Charles Borromeo, in cooperation with several NGOs, renovated a building on the eastern periphery of Johannesburg’s central business district in 2001 and made it a home for those fleeing their country of origin. . They named it the Bienvenu Shelter for Refugee Women and their Children.

No matter the situation at Bienvenu, the first 72 hours after the residents arrive are considered “emergency hours.” In most of these cases, women have experienced traumatic situations, such as human trafficking, war and torture. Some have panic attacks or anxious episodes, while others arrive with health problems.

“Sometimes the mother is as vulnerable as a child. If she came to the point that she came, it was not because she wanted to; but she had a little house, it was a small and simple house, but she was the mother of that house,” said Sister Adília de Sousa. “We have to start there, that she lost everything…..”

South Africa has stood out for its open arm stance toward refugees, with the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants calling the country a model for the continent in 2011. However, over the years, several UN human rights committees have expressed concern about the treatment of African migrants and refugees. In 2008, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights highlighted a pattern of xenophobic attacks and the UN Special Rapporteur on Racism expressed his dismay at the violence directed at migrants.

The prejudice creates an environment that increases police power and urges citizens to denounce “illegal migrants,” thus pitting poor black “natives” against poor black “foreigners,” according to Sr. Marizette Garbin MSCS, coordinator of the Department of Pastoral Care and Migrants at The Archdiocese of Johannesburg. “We see the need to integrate (migrant and refugee) in our society; to be positive actors in the process of social inclusion and for better social cohesion,” she said.

Integrating Africans from All Countries

With funds from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture, its Mother Assunta Training Center offers classes in sewing, basic and advanced, baking basic and advanced, make-up and nails, crafting for small business and providing domestic services to most people who qualify, including women who survived torture. English classes are also provided and these classes are based at the Archdiocese of Johannesburg.

As a former beneficiary, Marie Christine Uwera, says, “the approach can be summed up by the proverb, If you give me a fish, I will eat, but if you teach me to fish, I will not be hungry anymore.”

Bienvenu Shelter received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2006.

Stopping Torture Along Migration Routes

Collective of Associations Against Impunity in Togo (Togo)

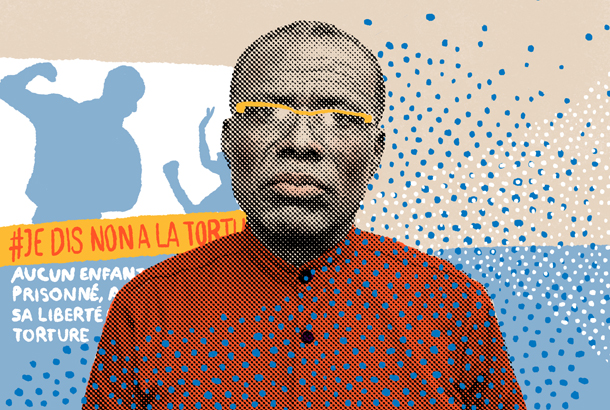

Akakpo Komi Adjété Djifa (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by CACIT)

“Thousands of migrants around the world risk their lives to cross international borders for safety. Many of these people have lost their lives or face injury in their desperate attempt at a better life. Most are in vulnerable situations,” said the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants, Felipe González Morales, in a 2021 report.

“There are important aspects of torture and ill-treatment experienced by people on the move in, across, and at the gates of Africa that have remained particularly under-explored and under-researched,” said Ghislain Nyaku, the Executive Director of the Collective of Associations Against Impunity in Togo (CACIT), which comprises fourteen associations and NGOs specializing in the defense of human rights of African migrants en route to new destinations. “This simply cannot be tolerated.”

Nyaku’s organization has put together a team of 25 lawyers working pro bono at the national, regional and international level to help refugees. CACIT also works with 10 African and European experts on migration and torture in Africa, and about 15 journalists who regularly follow its activities.

“We need to use our knowledge of, and unique access to, migrants in order to analyze first-hand information and set out authoritative research and recommendations for a protection agenda,” Nyaku said.

Picking Up Where States Leave Off

Thanks to theUnited Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture and CACIT, torture survivors have better living conditions and stronger legal protection. For several, including Komi Adjété Djifa, a non-commissioned officer of the Togolese armed forces, who was held and tortured by military forces in Togo after being accused of attempting a coup, CACIT “is like a light that offers (us) hope for better rehabilitation.”

“I received medical assistance which allowed me to treat myself, physically and to pay for my medical treatment,” he added. “My wife and children also benefited from support which has been very favorable to us in improving our autonomy. This collaboration has allowed many victims of torture, like me, to be alive today.”

CACIT and its affiliates have concluded that all States have to refrain from adopting laws and practices, such as blanket laws criminalizing mobility or other collective measures such as “pushbacks”, that blatantly negate the human dignity of affected migrants. They state that any migration law, policy or practice should mainstream an anti torture perspective or undertake a clear safeguarding policy.

In his 2021 report, Special Rapporteur González Morales demanded that governments abide by international law which prohibits collective expulsions and refoulement to a country where a migrant may face death, torture, ill-treatment, persecution or other irreparable harm.

“Torture on migration routes is not collateral damage. It is facilitated by national laws and policies that criminalize migrants,” said Isidore Ngueuleu, head of the OMCT Africa desk, a partner of CACIT. “The debate here is not whether or not to accept migrants into our societies. It is about ending this appalling cycle of torture, punishing the perpetrators and rehabilitating the survivors. Countries cannot turn a blind eye just because these people are not their citizens.”

The Collective of Associations Against Impunity in Togo (CACIT) received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2014.

Choices for New Life in West Africa

Rescue Alternatives Liberia (Liberia)

Akeelah* (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by RAL)

Acting on their own accord, Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) rebels in Liberia arrested Akeelah*, an innocent civilian, and charged her with harboring government soldiers. Despite her adamant denials of wrongdoing, LURD soldiers gang-raped Akeelah as punishment and left her in the bush. She walked four days to reach the capital of Monrovia.

“I had been going with this pain and trauma,” Akeelah said. “But I was recruited by my colleague who benefited from Rescue Alternatives Liberia’s services and brought me to the Torture Victims Rehabilitation Centre.”

In 2003, six years after the civil war, the UN Security Council called upon the Government of Liberia and all parties, particularly the LURD, to end the use of child soldiers and to prevent sexual violence, and torture.

“At the Centre, I received medical help, psychosocial counseling, and livelihood skills training. As a result of the services received, my medical condition greatly improved, which made the pain I experienced dissipate, as well as the trauma,” she added. “I am now contributing to the growth and development of my family in particular and the community as a whole.”

One Family

Rescue Alternatives Liberia (RAL) was formed in the early 2000s as a non-governmental organization that provides alternative strategies to enhance Liberia’s human rights record, contributing to the strengthening of the rule of law, and peace and democracy building. With support from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture, RAL provides holistic assistance to victims of torture, including rehabilitation designed specifically for survivors, in addition to counseling services, medication and livelihood skill trainings, such as hairdressing and baking.

"Put in practice what you have learned. Don't allow your talent to die down, we will continue to work with you because when you are empowered, people don't overlook you,” said Sam Nimely, the program coordinator of RAL. “People will respect you and you must do something positive. Count on us because we are now one family”

For the past 20 years, RAL has been a key player in shifting the national focus towards a more democratic future. For instance, it has shifted its focus from strictly recovery work to advocacy and partnered with Liberian legislators in submitting anti-torture legislation to the national parliament.

RAL has also openly denounced conditions in Liberia’s prisons and detention centres, called for reforms in their management, and advocated for the abolishment of the death penalty. Lastly, as abuse of power by the police has gained attention across the globe, RAL wants the Liberian Government to acquire the political will to punish law enforcement officers whose behavior has led to injury and death.

It's a big agenda, but Nimely believes RAL is up to the task. “There are treaties that the Liberian government has ratified over the years, and were accepted, but the government now has an obligation to comply with the international community in the implementation of those documents,” he said.

RAL received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 2003.

Coordinating Answers for Torture Survivors

Independent Medico Legal Unit (IMLU) (Kenya)

Professor Emily Rogena (illustration by Vérane Cottin, photograph by IMLU)

The morning of 12 August 2017 — the day after incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta was declared winner of the national elections — brought significant violence to Mathare, a sprawling slum in Nairobi. Teenagers threw rocks. Angry men waved fists. Armed police clustered around their trucks.

In the midst of it all lay a dead 10-year-old girl.

Determined in their pursuit of the girl’s alleged killers, the Kenyan Police Service shot dead nine young men and injured 30 people in “anti-looting operations”, according to the Reuters news agency. “They are criminals, and you must expect the police to deal with them in the way that criminals are dealt with,” said Fred Matiang’i, a Kenyan government official, explaining the heightened police brutality in the Reuters article.

Professor Emily Rogena disagreed. A leading forensic analyst for more than 20 years, including in landmark cases of exhumation involving victims of torture, Rogena concluded that the young girl’s death was the likely result of a stray police bullet. Although officially an employee of the Kenyan government, Rogena has proved fearless in criticizing its abuses. She also leads a team of the 25 doctors and pathologists in the Independent Medico Legal Unit (IMLU), which organizes against indiscriminate police killings, abusive evictions, lack of government accountability, and arbitrary arrests, beatings and torture.

The Power of a Collective Voice

Rogena gathered around two dozen colleagues and formed the IMLU to provide a framework for responding to cases of torture in Kenya. With assistance from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture, Rogena and IMLU — now a national presence of more than 300 doctors, trauma counselors, lawyers, human rights monitors, and journalists — have supported more than 6,000 victims of torture, cruel, degrading, and inhumane treatments. IMLU employs litigation, medical and psycho-social rehabilitation, socio-economic empowerment, surveys government compliance with human rights obligations, and advocates for reforms that promote accountability, healing and justice.

“It is utterly disappointing that 11 years after the promulgation of Kenya’s 2010 constitution that has universally been acclaimed as the most progressive, the government has deliberately shown attempts to water it down…,” said Rogena.

Abuses continue, particularly over the past two years as police try to enforce COVID-19 measures. At least 3 deaths and 61 injuries as a result of police violence were documented within the first 10 days of the curfew. IMLU conducted 19 autopsies and prepared forensic and legal documentation which is critical in criminal proceedings and redress lawsuits.

“Everyone has a right to protest peacefully and therefore the government and its agents, the police, should see to it that human rights are not violated in the pretext of managing dissenting voices,” Rogena said.

IMLU received its first grant from the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture in 1997.

VIEW THIS PAGE IN: