Surviving torture: “I choose life every day”

24 June 2024

“I was born into a family with a very strong social conscience, especially my father,” said Emma Molina Theissen, a 64-year-old Guatemalan human rights activist.

“Soon my sister Lucrecia and I began our activism,” Molina Theissen said. “In the context of the Cold War, the Latin American strategy of repression against social movements, against the ‘communist threat’, included enforced disappearances.”

By 1976, Guatemala was suffering what came to be known as an internal armed conflict that lasted more than 30 years, from the late 1960s until the peace accords were signed in 1996.

That same year, an earthquake left more than a million people homeless and provoked massive internal displacements and misery belts around Guatemala City.

“[This situation] really fuelled social discontent. I was about to turn 16 at the time and was already participating in a student movement that began to grow very strongly,” Molina Theissen said.

While the students were committed to helping those affected by the earthquake, they also promoted their ideological views.

“While handing out leaflets in a settlement of displaced people, we were captured, a comrade who was with us, a 17-year-old boy, was killed, and another one was wounded in the spine. She is still in a wheelchair,” Molina Theissen said.

Molina Theissen described the torture she survived at the hands of the police, including violent interrogations and a rape, during this arrest. After her release, she continued to fight for social change. In 1980, Molina Theissen’s fiancé was murdered along with three other university students.

“They took them, tortured them, murdered them, fortunately, and it's horrible to say that, but fortunately their bodies turned up on that same day,” said Molina Theissen. “It was a terrible blow. We had been together for five years. We were going to get married in a few weeks.”

By then, Molina Theissen felt she was in danger because she was known to the military regime. She left the capital and went to Quetzaltenango, in northwestern Guatemala.

Even when many activists had left, under a new identity, Molina Theissen continued to fight. By 1981, activists disseminated flyers reflecting their dreams of a better country. In her dissemination efforts, Molina Theissen regularly went from Quetzaltenango to Guatemala City. She was later detained and taken to the military base in Quetzaltenango.

“Torture is an affront to human dignity and an attack on the very core of the human being,” said Mahamane Cisse-Gouro, Director of the Human Rights Council and Treaty Mechanisms Division at UN Human Rights. “This is the reason why States have agreed, as a consensus, that the right to be free from torture should be one of the few human rights which is absolute. This means that there are no exemptions – the right to be free from torture applies in all circumstances, at all times, to everyone.”

Nine days in captivity

“They took me to a place that I think was where the officers slept. And then violent interrogation sessions, sexual violence and mistreatment began,” Molina Theissen said.

Handcuffed to a bunk bed, stained by her own urine, dehydrated, hungry and scared, Molina Theissen somehow tried to stay calm.

“One day, the guy didn’t show up to interrogate me and I started to think they're going to kill me. I spent that whole day alone and when it started to get dark, I completely lost it and, in a panic, I managed to get out of the handcuffs,” Molina Theissen said.

Once she ran away, her first impulse was to return home to her family, but she decided to go to her friend’s house instead. The next day, members of the military came to look for her at her family's home. Since they didn’t find her there, they took her 14-year-old brother, Marco Antonio, who is still disappeared.

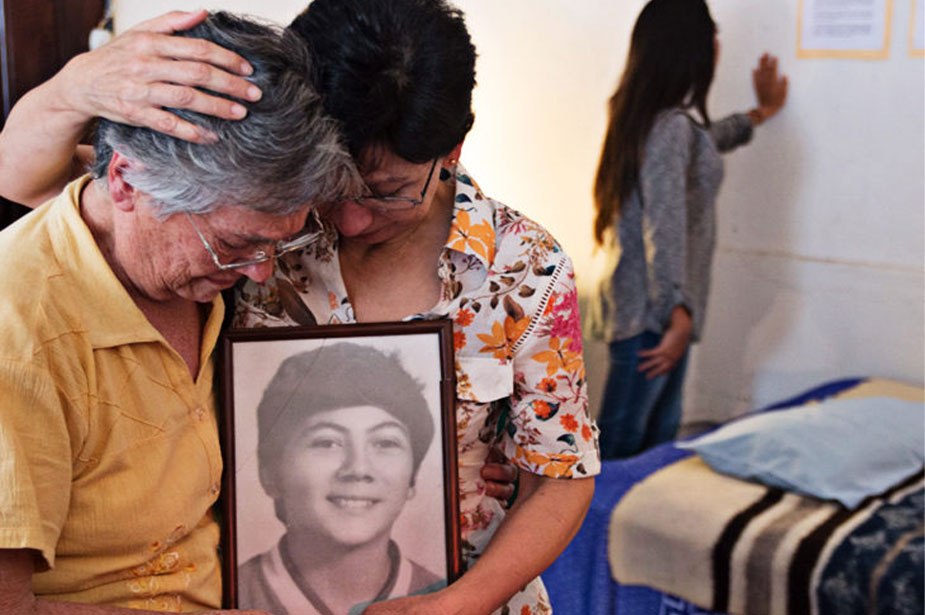

María Eugenia Molina Theissen, her mother and the photo of Marco Antonio Molina, a victim of enforced disappearance. © Kimmy De León / Prensa Comunitaria

Molina Theissen had to flee to Mexico, where she learned about her brother’s disappearance in 1982.

Back in Guatemala City, in 1984, her family survived a brutal persecution. Her sister's husband was beaten to death. Some of her family went into exile to Ecuador and her other sister moved to Mexico City. Molina Theissen later received a scholarship to move to Costa Rica, where the whole family was eventually reunited. Molina Theissen has lived in Costa Rica for almost 40 years. While she feels safe, the disappearance of a loved one is another kind of torture.

“Yes, it is a psychological torture because we constantly experience a tremendous feeling of guilt that does not go away,” Molina Theissen said.

In pursuit of justice

Molina Theissen’s family tirelessly searched for Marco Antonio and sought justice with the help of the Center for Justice and International Law, a human rights NGO beneficiary of the UN Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture. These efforts led the case on the disappearance of Marco Antonio to reach the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

In 2004, the Court condemned the Guatemalan State for the enforced disappearance of Marco Antonio. In 2018, a Guatemalan court sentenced four former members of the military for Marco Antonio's disappearance and the sexual violence endured by Molina Theissen.

The Committee against Torture (CAT) is the body of 10 independent experts that monitors the implementation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment by its States parties. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Convention, which was adopted in December 1984. On 26 June, the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture marks the moment when the Convention came into force.

The CAT works to hold States accountable for human rights violations, thoroughly investigating reports of torture to stop and prevent this crime.

In a report on Guatemala in 2018, the CAT recognised progress made by the State in some cases involving grave human rights violations committed during the internal armed conflict, including the Molina Theissen Theissen case.

The CAT highlighted that the State needed to step up its efforts to locate and identify all persons who were subjected to enforced disappearance during that period by setting up a national search commission and a consolidated, centralized register of disappeared persons.

Relatives of the disappeared have been considered to be victims of torture by the CAT and many other international and regional bodies, given the immense suffering that comes about from not knowing the fate and whereabouts of a loved one.

The Molina Thiessen family display a photo of their brother while holding a banner that includes the number of signatures they’ve received so far asking for truth and justice in Guatemala. Credit: © CEJIL

“Torture is not an isolated phenomenon, but in many cases is associated with other human rights violations such as arbitrary detention or extrajudicial executions,” said Claude Heller, Chair of the CAT.

The Convention has been ratified by 174 States but according to Heller, there is not a single State in the world that’s free of torture, directly or indirectly, however, progress has been made, mainly in terms of legislation.

“Beyond the specifically focused anti-torture mechanisms, UN Human Rights also supports the work to prevent and eradicate torture, though through different lenses, such as women’s rights, children’s rights and the rights of persons with disabilities,” Cisse-Gouro said.

The Office acts as a hub facilitating collaboration and coordination between them, ensuring concerted efforts against torture across the whole UN human rights ecosystem.

For Molina Theissen, torture survivors also need to find the strength to rebuild themselves, no matter what they want to do in life.

“Because if we don't find that strength, we are dead. And the torturers will have finished their task because they will have destroyed us completely,” Molina Theissen said.

Disclaimer: The views, information and opinions expressed in this article are those of the persons featured in the story and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.