Child and forced marriage: a violation of human rights

03 November 2016

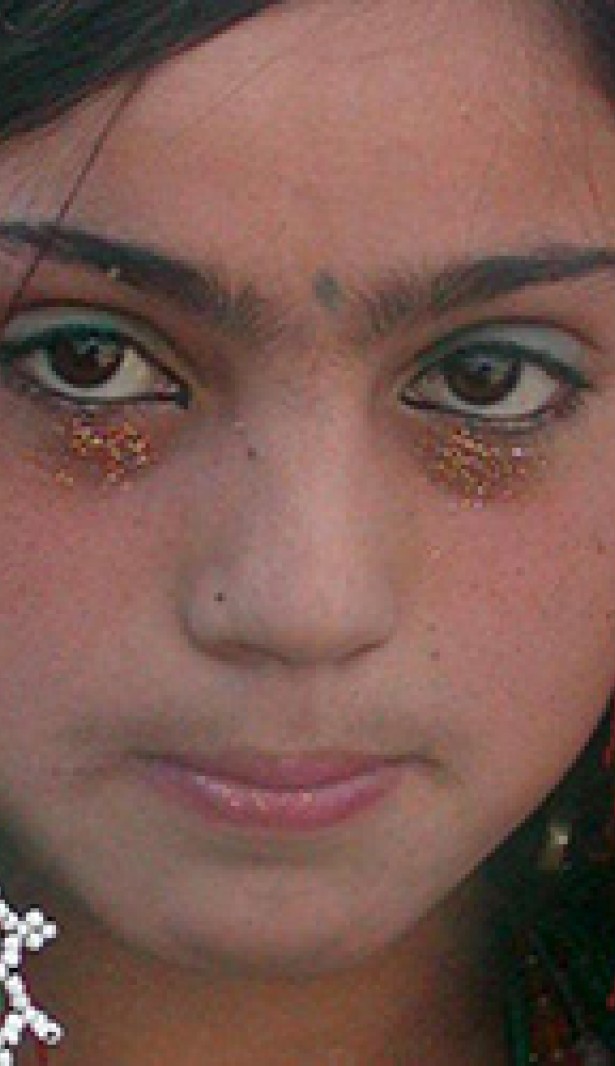

“When it came my time, I just asked my dad to please let me go one more day to school,” Sorina Sein says, her voice breaking, as she tearfully recounts her story of being forced to marry at the age of 13.

Growing up in a Roma community in Romania, she was faced with no option but to go along with the wishes of her father. On the appointed wedding day, Sein decided to chop off her long hair. “I had beautiful, long hair, and to cut my hair was a trauma for me,” Sein recalls. Her quiet act of resistance resulted in the groom’s family rejecting her as a bride.

“They said our boy cannot marry this girl. She’s crazy,” Sein recalls. “I told them no, I’m not crazy. I just want to go to school. I want to play, I want to be with my friends,” she says. “I told them I don’t want to cook or have children. I want to have an education.”

Sein’s defiance caused a scandal in her family, but she went on to finish middle school and high school, before pursuing a university degree in political science. At 34, she continues to campaign single-handedly to end the practice of child marriage in her community.

“This practice is a crime for children. It makes them victims for all their lives,” Sein told a panel of experts gathered recently at an OHCHR Expert Workshop in Geneva to discuss the impact of regional and national efforts to eradicate child and forced marriages.

Today, about 700 million girls worldwide are married before they reach adulthood, according to UN estimates. By 2030, if the practice continues at the current rate, this number will grow to as many as 950 million, says Veronica Birga, chief of OHCHR Women’s Rights and Gender Section. In July 2015, the Human Rights Council adopted its first substantive resolution recognizing child and forced marriage as a human rights violation.

“Child and forced marriage represents a violation of virtually all human rights,” says Birga. “It deprives women and girls of autonomy and choice over their bodies and their lives.”

Girls forced into marriage are exposed to early pregnancies that are detrimental to their health because their bodies are not ready. Child marriage also has serious impacts on education because girls are often withdrawn from school to be married off, or they drop out of school after they become pregnant. “This has the effect of perpetuating the cycle of poverty and exclusion,” says Birga.

Theresa Kachindomoto, senior chief of the Dedza District in Malawi, has made it her top mission to abolish the practice of child marriage in the 551 villages in her area. Malawi has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world, where 50 percent of girls are married before they reach adulthood. Even before Malawi’s parliament passed a law last year prohibiting marriage before the age of 18, Kachindomoto has devoted the past decade using her authority as a custodian of tradition granted to Malawi chiefs to outlaw child marriage in her area. Last year, Kachindomoto convinced 50 village heads to sign an agreement to prohibit and annul child marriages in their villages. She has dismissed five village heads for failing to observe the prohibition and allowing girls to marry.

Working with village leaders and a network of parent groups , Kachindomoto has succeeded in breaking up 1,455 child marriages, gaining her a reputation as a fearless “marriage terminator”. In a country where marrying off a daughter is often seen as a way to gain family resources, Chief Kachindomoto is going to door-to-door to convince parents to keep their girls in school and send young mothers back to the classroom.

“I tell the parents if you educate your girl child, she will take care of everything,” says Kachindomoto. “When you educate a girl child, you educate the whole area.”

Her efforts have met with some resistance, resulting even in death threats, she adds. But Kachindomoto remains unfazed and is pushing ahead with her mission. She is lobbying now to amend Malawi law to push up the minimum age of marriage to 21. Next up in her campaign to keep girls in school, she says: “What about college?”

3 November 2016