An antidote against unjust societies

29 September 2016

Over ten years ago, human rights educators in India started teaching school children about their rights, the principles of non-discrimination, and equality and how they apply to their daily lives.

Premalatha, a young human rights student from a small village in Tamil Nadu, Southern India, is one of 300,000 Indian children who have benefited from initiatives supported by the UN human rights education and training programme, the Government and civil society.

“In my village, my family is lower caste,” explained Premalatha. “My mother is a construction labourer; my father, a truck driver. They make me do all the work- never my brothers; only boys are valued and supported in our family.”

Thanks to her education, Premalatha has a new outlook on centuries-old traditions that linger throughout India. “I think being born a girl is not a problem,” she said. “I have been denied my rights. But these rights are my birth right. Since I studied human rights I want to become a teacher. I want to teach human rights.”

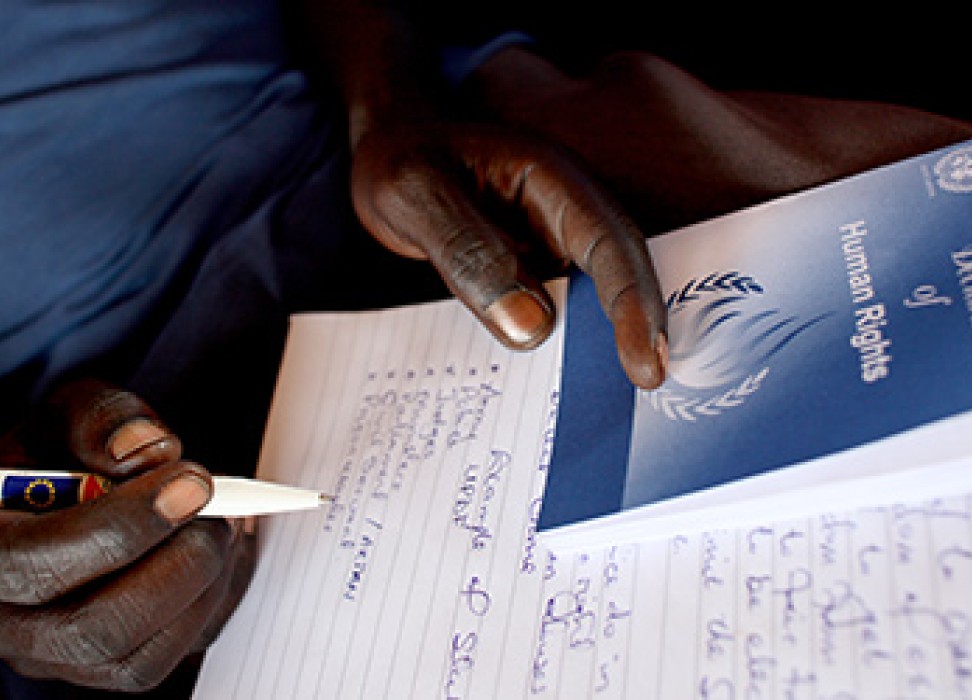

Five years ago, the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training, under the premise that education promotes values, beliefs and attitudes that encourage all individuals to uphold their own rights and those of others.

Advocates believe that human rights education can contribute long-term to the prevention of human rights abuses, and is an important investment for a just society in which the rights of all are valued and respected.

During the latest session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, experts reflected on the achievements, five years on, and possible improvements that could be made to the human rights education programmes promoting these universal standards around the world.

Opening the panel, the UN Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights, Kate Gilmore, recalled that the adoption of the Declaration was part of a standard-setting process that started with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which tasked each individual and institution to promote human rights through education.

“The good news is that this is happening,” she said. “A recent report issued by my Office in the context of the World Programme informed that, in some countries, institutions increasingly pursue human rights education programmes, with better tools and methodologies and with growing cooperation within government departments and among governments, academia, national human rights institutions and non-governmental organizations.”

In Costa Rica, human rights education is rooted in the country’s pacifist tradition, pointed out the Minister of Education, Sonia Marta Mora Escalante. Abolishing the army and investing in 2014 eight percent of the national GDP in education was, she said, an unequivocal sign of the will to build a culture of peace based on respect for human rights.

Mora Escalante described the case of a 13-year-old who was refused entry to school because he wore his hair in dreadlocks. After analysing international conventions and national law, the Ministry repealed the school’s internal rule which affected people’s cultural identity “in recognition of the cultural specificities of the black population, allowing students like this young man, who came to our authority, to freely express their cultural identity.”

In 2003, Brazil adopted its first National Plan for Human Rights Education after implementing human rights education policies during the past two decades. Successive Plans served as guiding tools for areas such as basic education; higher education; informal education; education for justice system and law enforcement officials; and education for the media.

“Having recognized and embraced human rights education as a human right itself, it is imperative to adopt and apply it as a means to empowerment and as a source of inspiration for social change, given the transformative and emancipatory power of human rights education,” said Flavia Piovesan, Secretary for Human Rights at the Ministry of Justice of Brazil.

She added that the persistence of human rights violations can be explained by the existence of cultures of abuse and violence. “The best answer – the actual antidote – is the shift from these cultures of violation to cultures of promotion of rights. In order to do so, the most effective tool is indeed, human rights education.”

For Driss El Yazami, Chair of the National Human Rights Council of Morocco, education and training are highly significant in guaranteeing the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. If a country had educated citizens who knew about their rights, he pointed out, this would be a step towards democracy.

The Centre for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence in Montréal, Quebec, Canada, takes charge of radicalized individuals and works with their families to rehabilitate them, and instil in them a sense of empathy for fellow human beings.

Executive Director, Herman Deparice-Okomba, pointed out that preventing violent extremism requires ensuring that human rights continue to influence the social and political life in our societies.

“All our educational tools, activities, training and awareness workshops aim to promote understanding, tolerance, gender equality and living together,” he described. “We encourage our young to participate in democratic life, and develop citizen attitudes and behaviours of openness, respect and acceptance of diversity.”

29 September 2016