The crisis in the Horn of Africa: a human rights perspective

26 October 2011

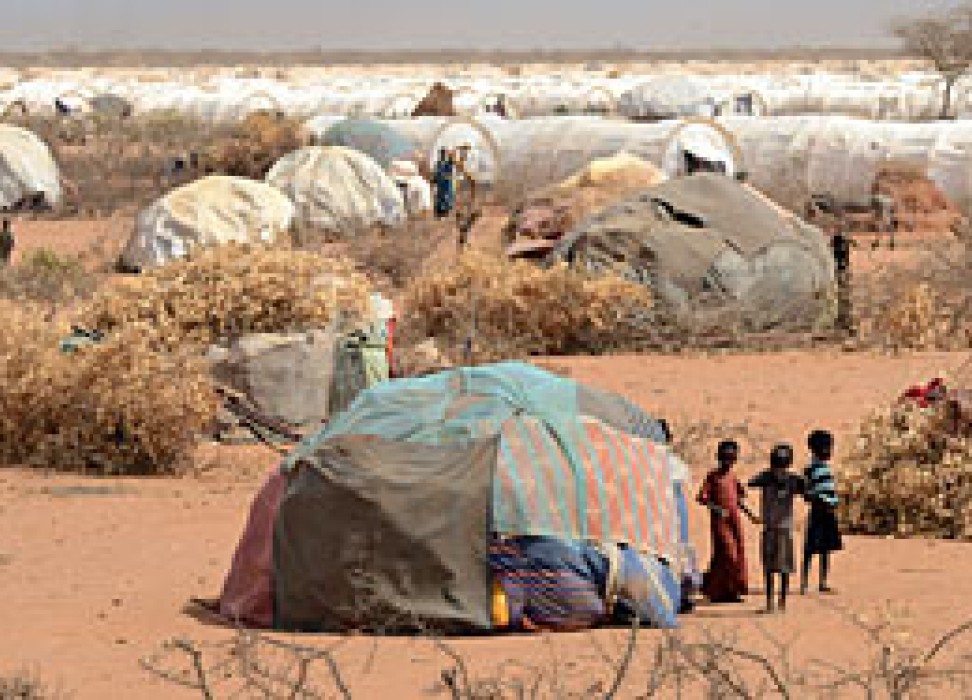

About 13.3 million people in the Horn of Africa—Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, and eastern Uganda—have been affected by a devastating drought. At this very moment, a mother is faced with the unbearable choice of which child to let die and which one to keep alive.

“The temptation to look at the victims from a numbers perspective is strong, but we have to resist it,” said UN Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights Kyung-wha Kang. “Behind every number is a human being in intolerable distress.”

Human rights experts examined the human rights dimensions of the crisis in the Horn of Africa at an event during the 18th Human Rights Council session moderated by Council President Dupuy Lassere.

Reminding participants that providing adequate financial resources for the emergency operation was the collective duty of the international community, Kang called for humanitarian assistance that “did not create a dependency on external inputs, but empowers people to rebuild their capacity to produce or procure adequate food in a sustainable manner.”

“If we genuinely want to address the crisis and prevent it from ever happening again, there is a responsibility for all of us, as individuals and for the institutions we represent, to analyse the complex and multiple causes of this crisis and to adopt a multifaceted approach to addressing them. The crisis we are facing is not only a food crisis, but fundamentally a human rights crisis,” Kang said.

Kang mentioned the armed conflict in Somalia, characterized by massive violations of human rights and humanitarian law, as a key cause of the current crisis. According to UNHCR, about 300,000 Somalis have fled to neighboring countries in 2011 alone.

Tom Mboya Okeyo, the Ambassador of Kenya to the United Nations, said that “since the early 1990s, when the humanitarian protection force withdrew from Somalia, the international community has been unable to agree on a proactive and energetic approach for dealing with Somalia.” He urged the Security Council to take decisive action on Somalia and to strengthen the African Union Mission in Somalia. The Independent Expert on the situation of human rights in Somalia, Shamsul Bari, pushed for sanctions to be enforced on countries that continued to finance, facilitate and execute terror.

Speaking on behalf of Olivier De Schutter, Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Bari underscored the need for better drought-preparedness and government accountability. “Human rights concerns include lack of good governance and lack of inclusive participation in public affairs,” he said. Oxfam representative Aimee Ansari pointed to the insufficient investment in small producers as the cause of the food insecurity in the region.

Mboya called for the implementation of the Nairobi Action Plan on the Horn of Africa. “The binding Action Plan,” he said, “represents the political commitment at the highest level by States from the sub-region to integrate risk-reduction and climate change adaption into their development planning and resource allocation.”

Speaking about the negative impact of high food prices on the Horn of Africa, Kang called for an equitable distribution of world food supplies and emphasized the responsibility of the international community to enable developing countries to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Kang also cited the importance of reflecting on the way in which foreign aid and development assistance had been delivered, adding that the crisis has provided an opportunity to examine grievances such as the debt burden, trade, representation in international financial institutions, toxic waste dumping, and illegal fishing.

“The humanitarian disaster risks becoming another blot on the conscience of mankind,” Bari said.

26 October 2011

VIEW THIS PAGE IN: