We have to figure out how to dismantle the monster

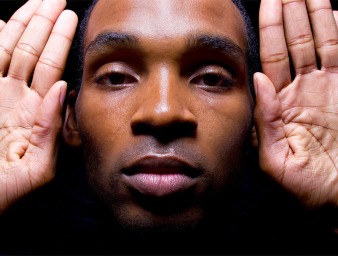

Tenoch Huerta said it was a name that made him realize not only the insidiousness of racism, but that he had also been conditioned to accept it.

“The breaking point was when my niece, who was six-years-old at the time, who is my same skin colour, was severely discriminated against at school,” he said. “They called her “la Negra” (Black girl), but they didn’t do it with affection. “

Huerta explained that growing up he was called “Negrito” (little Black boy) by his family, but it was an affectionate nickname. But he realized the nickname could also wound, when it’s used as a slur. His niece changed schools and was happier. And Huerta began to rethink his relationship with words, particularly racially charged ones and what he could do about them.

"There were many things, an accumulation of experiences, of knowledge, of reflections,” Huerta said. “It is a painful process to realise that you not only received violence but that you exercised it. In my case, it has been more painful to recognise that I have exercised it than that I have received it."

Now internationally known for playing Namor in the Hollywood blockbuster Wakanda Forever, Huerta is an anti-racist fighter who uses his media platforms to discuss and report on various manifestations of racism and racial discrimination and how to fight against them.

In Mexico, Huerta is part of an organisation called Poder Prieto (Brown Power in English), which covers four areas: representation, social practices, information and training, and law. Huerta works in the area of representation and is convinced that the way Brown people are represented influences the way they are treated on a daily basis. The word Prieto is normally a slang taunt for people of colour living in Mexico. But Huerta’s organization seeks to reclaim the word removing the racial and classist connotations surrounding it.

“The right to be who we are”

Anti-racism is not new, Huerta said.

“[It was] born 500 years ago, when people resisted the invasion of colonialism,” he said. “It had other names, defence of territory, defence of identity, defence of language, but in the end it was all about the same thing: defending the right to be who we are".

Huerta said racism and discrimination is so embedded in much of Mexican society, that it can be difficult to acknowledge and address.

"Normally, the one who discriminates against you the most is your family,” he said. “It's your grandmother who says you have to ‘improve’ the race” by marrying someone of a lighter complexion. “You get that from the people you love the most and you pass it on, that's why it becomes so painful to accept it.”

Huerta said it took him years to fully understand the racism inherent in his upbringing and culture, accept it, and to embrace his identity and work daily to fight his cultural conditioning.

“[Becoming anti-racist] is a process of reconciliation. It's slow, it's painful. But once it happens, it feels great,” Huerta said. “These processes help us to exercise our right to be happy."

"A lot of melanin on the screen"

Huerta's acting career began in 2006 in Mexico. He worked in several films and TV series until he starred in Días de Gloria (2011), directed by Everardo Gout, who, in 2021, cast him as the lead in the fifth instalment of Hollywood’s The Purge franchise, The Forever Purge. This role added to regional recognition following his role in the series Narcos Mexico (2018). Then came Wakanda Forever.

According to Huerta, Brown actors in Mexico would always be cast as thieves, people living in poverty, criminals, etc., with no character development or influence in the plot.

Producers, directors, filmmakers have told Huerta that proper representation of people of colour in films is a difficult challenge. He said this isn’t true.

“

Representation has become an unnecessarily problematic issue,

“

he said.

He cited as an example the casting of a Black woman to play the role of Ariel in the live-action version of The Little Mermaid. Most of the uproar over the casting came from people over 40, who said the casting “ruined their childhood,” Huerta said. But those under 40 were, for the most part, happy with the choice.

“[Resistance to diverse representation on screens] comes from certain generations who were educated and normalised in a type of narrative," he said. “For example, there is a publicist [in Mexico] who says that people only want to see beautiful people and the only beautiful people were white people."

“There was a lot of melanin on screen,” he said. “So where is it that people don’t want to see Brown people? This film proves that it’s not true. It’s normal for people to want to see themselves [on screen].”

Who is telling the story?

While on-screen representation is important, it is the people behind the stories being told who carry the narrative, Huerta said. In Wakanda Forever, he was instrumental in ensuring that Mayan culture (which was the culture of the group for which is character was based on), was properly represented via rigorous vetting by academic and cultural experts.

"They hired Mayan people who are Mayan-speaking and academically strong. They hired them and they brought their academic knowledge to say 'this is how [the Maya] were', and the knowledge of everyday life to say 'this is how we are'. That's why the film has withstood all the analyses of how the characters are represented because it had its inhabitants constructing their space," he said.

Huerta said that the storyteller’s skin colour is not the only element to take into account since "reducing it to skin colour is also a mistake, because if suddenly you have a guy who is Brown and comes from elite schools and behaves and identifies with whiteness - which has nothing to do with the colour of white skin, it has to do with the way of thinking - it's no use for him to be there. It has to come from the same places that most people come from."

“How to dismantle the monster”

In 2022, UN Human Rights launched the campaign "Learn, Speak Up and Act!", which aims to raise awareness about racism, xenophobia, racial discrimination and other forms of intolerance, under the premise that the problems are known and the solutions are known, but what is needed are concrete actions at all levels: at home, at school, in institutions, in the private sector, etc.

Huerta said that there has been progress in the fight against racism and is convinced that there are very concrete actions that can be carried out, from the personal, institutional, in public policies, private initiative, or in civil society organisations.

"I am very happy that now, at the slightest provocation, people on social networks say, ‘this is racism because of this and this’. I feel very positive for the new generations,” he said.

“I feel very happy that six years after my niece received those attacks, [now] we live in a country that already talks about it, that already recognises it, at least, now we have to figure out how to dismantle the monster."

And for young people struggling with issues based on race, skin colour or other forms of discrimination, Huerta had this message.

“When you look at yourself and see your reflection, think that there was nothing wrong with you instead with the eyes that looked at you.”