Security at forefront as Italian island receives migrants

18 July 2016

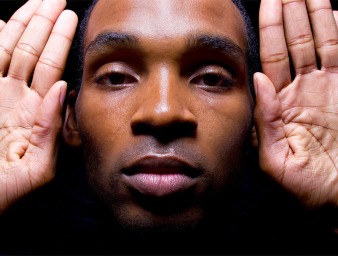

The young man, a blanket draped around his shoulders, steps off the Italian Coast Guard boat that has just docked in Lampedusa harbour. He will be asked his name and nationality in due course but for now, let’s call him Adam.

A doctor checks Adam’s hands and abdomen for signs of scabies, a highly contagious skin infection. He is then told to stand in line with dozens of other migrants rescued at sea and brought to this tiny island, Italy’s southernmost point some 113 kilometres from the Tunisian coast.

It’s a well-honed procedure. So far this year, Italy has given shelter to more than 70,000 migrants rescued while attempting to cross the Mediterranean from North Africa.

“The problem shouldn’t be that of Italy alone. There is an urgent need for more solidarity from the rest of Europe,” said Pia Oberoi, the UN Human Rights Office’s Advisor on Migration and Human Rights, who was part of a monitoring team that visited Italy to assess the human rights situation of migrants and refugees.

The scene at the landing stage is busy as staff from Lampedusa’s migration centre organise the disembarkation alongside Italian police and some dozen officials from the European border agency, Frontex, and the European Union’s Asylum Support Office, EASO. A representative from Save The Children puts his arm around the shoulder of a teenager, reassuring him that he is safe. There is little noise. Most of the migrants are exhausted; some are in shock. Adam too is quiet but he can’t stop smiling.

Initial checks complete, Adam and the other migrants board two vehicles to the Lampedusa “hotspot,” a closed reception centre where further health checks are carried out and where Italian police and Frontex officials register the migrants, taking fingerprints and photos and asking questions to try to determine identity, nationality, why they left and, in the case of those who may be children, their age.

The hotspot approach was established by the EU in Italy and Greece to speed up and organise the process of evaluating what should happen to migrants – whether they qualify for asylum, should be returned to their countries of origin or whether further investigation of their situation is required. The process should also, in theory at least, help to identify people who could be relocated to another EU member state.

Italy’s efforts to cope with the high but fairly constant numbers of arrivals over the past years are to be applauded but the emphasis on security is a concern, said Oberoi.

“The problem is that Europe has collectively decided to apply a security focus to the problem, to say the issue is one of border control and expulsion rather than, as we would expect it to be, an issue of the protection of the human rights of every person that arrives brutalised and traumatised by their journey,” she said.

Oberoi and other members of the UN Human Rights Office mission visited the Lampedusa centre and gathered testimonies from migrants about their journey and what had happened to them since arriving in Italy.

“We appreciate that the hotspot procedure is meant to be fast in order to process people through the reception system as quickly as possible but we are concerned at the lack of capacity to identify people who are especially vulnerable, such as victims of sexual and gender-based violence, of trafficking, of torture, of trauma, and to give them the help and support they need,” Oberoi stressed.

“There is also the risk that without a proper individual assessment, people from some countries are automatically viewed as ‘undeserving economic migrants’ rather than a person in need of human rights protection due to the abuse they have suffered in their own country or en route,” she added.

“We were struck by the fact that there are far more people involved in the identification process compared with those who can give medical, psychological or legal support,” said Oberoi. “A small adjustment in staffing to include, for example, more child protection experts, would help to address some of our human rights concerns.”

Adam and the others are driven through the metal gate at the hotspot. Inside, they sit on benches as they wait to undergo identification, including fingerprinting, and further medical checks. After that, they will be able to have a shower and a meal, get clothes and recuperate. Adam's journey is far from over and his future far from clear, but, for now at least, he can rest in this small corner of Italy.

This is the first article in a four-part series about the mission to Italy by UN Human Rights Office team from 27 June to 1 July. Read the other stories here:

- Migrants cling to their dreams as they await uncertain future

- Italy’s migrant hotspots raise legal questions

- Child migrants’ future in Italy “must not depend on luck”

18 July 2016