Module 11: Critical voices

#Faith4Rights toolkit

Full text of commitment XI

| We equally commit not to oppress critical voices and views on matters of religion or belief, however wrong or offensive they may be perceived, in the name of the “sanctity” of the subject matter and we urge States that still have anti-blasphemy or anti-apostasy laws to repeal them, since such laws have a stifling impact on the enjoyment of freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief as well as on healthy dialogue and debate about religious issues. |

Context

Oppression of dissenting views also occurs among religious actors themselves. This shows, once more, the degree to which the freedom of conscience is not always respected. Freedom of expression applies equally to the religious sphere. Every person is entitled to his or her own views. This simple fact seems far from being the mainstream practice in the religious sphere. Even more dangerously, anti-apostasy and anti-blasphemy laws, most of which predate modern human rights norms and standards, are used against freedom of thought, conscience, religion, belief, opinion, expression and peaceful assembly of individuals on religious matters across regions and religions. Such laws are also often used to crush political opposition and various minorities.

Additional supporting documents

In support of the module on commitment XI, the training file should include UN Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 34 of 2011 (“Prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with the Covenant, except in the specific circumstances envisaged in article 20, paragraph 2, of the Covenant. Such prohibitions must also comply with the strict requirements of article 19, paragraph 3, as well as such articles as 2, 5, 17, 18 and 26.”). Furthermore, the Rabat Plan of Action notes that “19. At the national level, blasphemy laws are counterproductive, since they may result in de facto censure of all inter-religious or belief and intra-religious or belief dialogue, debate and criticism, most of which could be constructive, healthy and needed. In addition, many blasphemy laws afford different levels of protection to different religions and have often proved to be applied in a discriminatory manner. There are numerous examples of persecution of religious minorities or dissenters, but also of atheists and non-theists, as a result of legislation on what constitutes religious offences or overzealous application of laws containing neutral language. Moreover, the right to freedom of religion or belief, as enshrined in relevant international legal standards, does not include the right to have a religion or a belief that is free from criticism or ridicule. […] 25. States that have blasphemy laws should repeal them, as such laws have a stifling impact on the enjoyment of freedom of religion or belief, and healthy dialogue and debate about religion.”

In 2019, Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed acknowledged that “several countries, including Norway, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and, most recently, Denmark, Malta, Ireland and Canada have repealed anti-blasphemy laws”.

Furthermore, the 2019 report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Ahmed Shaheed, explores freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression as two closely interrelated and mutually reinforcing rights: “International law compels States to pursue a restrained approach in addressing tensions between freedom of expression and freedom of religion or belief. Such an approach must rely on criteria for limitations which recognize the rights of all persons to the freedoms of expression and manifestation of religion or belief, regardless of the critical nature of the opinion, idea, doctrine or belief or whether that expression shocks, offends or disturbs others, so long as it does not cross the threshold of advocacy of religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence.”

The Special Rapporteur stressed in a press release that “criticism of the ideas, leaders, symbols or practices of Islam is not Islamophobic per se; unless it is accompanied by hatred or bias towards Muslims in general”.

The Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, David Kaye, stressed in his 2019 report the following: “Some restrictions are specifically disfavoured under international human rights standards. As a first example, the Human Rights Committee noted that “prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with the Covenant”, except in cases in which blasphemy also may be defined as advocacy of religious hatred that constitutes incitement of one of the required sorts. To be clear, anti-blasphemy laws fail to meet the legitimacy condition of article 19 (3) of the Covenant, given that article 19 protects individuals and their right to freedom of expression and opinion; neither article 19 (3) nor article 18 of the Covenant protect ideas or beliefs from ridicule, abuse, criticism or other “attacks” seen as offensive. Several human rights mechanisms have affirmed the call to repeal blasphemy laws because of the risk they pose to debate over religious ideas and the role that such laws play in enabling Governments to show preference for the ideas of one religion over those of other religions, beliefs or non-belief systems”.

In 2013, the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Farida Shaheed, noted that “Restrictions on artistic freedoms based on religious arguments range from urging the faithful not to partake in various forms of artistic expression to outright bans on music, images and books. Artists have been accused of “blasphemy” or “religious defamation”, insulting “religious feelings” or inciting “religious hatred”. Artistic activities or artworks concerned include those quoting sacred texts, using religious symbols or figures, questioning religion or the sacred, proposing an unorthodox or non-mainstream interpretation of symbols and texts, adopting a conduct deemed not to follow religious precepts, addressing abuse of power by religious leaders or their linkage with political parties or criticizing religious extremism. The Special Rapporteur recalls that “prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with [ICCPR], except in the specific circumstances envisaged in article 20, paragraph 2, of the Covenant.” Blasphemy laws have a stifling impact on the enjoyment of freedom of religion or belief and impede a healthy dialogue and debate about religion.[footnote referring to the Rabat Plan of Action]”. Several Special Rapporteurs also stressed that “Music is not a crime” in their 2020 press release urging Nigeria to overturn the death sentence given to a singer who had shared a song on WhatsApp.

Peer-to-peer learning exercises

Unpacking: Participants break down commitment XI into different elements. They list corresponding action points and which actors should be responsible for implementing them. (individual exercise for five minutes followed by ten minutes of a full group discussion on the differences between individual listings).

Linking the dots: Participants may discuss the relationship between these elements and responsibilities, starting with the underlying formulation in paragraphs 19 and 25 of the Rabat Plan of Action, as quoted above in the additional documents (collective exercise for 10 minutes). The key dots that require linking through discussions on commitment XI include: anti-blasphemy laws versus freedom of expression, do religions need “protection”, and can domestic anti-apostasy laws be in compliance with freedom of thought, conscience, religion and belief?

Commitment XI is at the heart of the “Faith for Rights” framework. It is essential for the fulfilment of all other 17 commitments. Its relations to other commitments are analogous to that linking freedom of expression to all other human rights.

Critical thinking: The facilitator may ask participants if they disagree with any of the elements. Can any of them stand alone? Are there missing elements in commitment XI? Are there examples of religious texts which call for punishing blasphemy and apostasy? Is there an established definition and a threshold of blasphemy, if ever defined? Are there religious texts that require believers to “defend” their religion? Related to this point, the facilitator could critically discuss with participants the penultimate paragraph of the Marrakesh Declaration, which calls “upon representatives of the various religions, sects and denominations to confront all forms of religious bigotry, villification, and denegration [sic] of what people hold sacred […]”. Furthermore, the Cairo Declaration of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation on Human Rights (as revised in 2020) provides in its article 21 that “freedom of expression should not be used for denigration of religions and prophets or to violate the sanctities of religious symbols”. Questions for the facilitator to animate a discussion on this point could also include whether religions or religious symbols need human protection? Against what? How can one distinguish “denigration” from criticism, regardless of its possible lack of sensitivity? Should a believer be offended because somebody does not share and even criticizes his or her belief? Would this be compatible with commitment I on the absolute freedom of conscience?

In this regard, the facilitator could also quote the 2019 report of Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed: “Some anti-blasphemy laws no longer claim to protect religions per se but claim to protect individuals from offence to their religious feelings. These laws against the defamation of religion, however, also have no basis in international law, as such restrictions do not comply with the limitations regime established by international law.” Furthermore, in March 2021, five Special Rapporteurs criticized article 21 of the revised Cairo Declaration, stressing that “States must not revive the dangerous notion of 'defamation of religions'” and that “the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief has emphasised in his most recent report to the Human Rights Council that criticism of the ideas, religious leaders, symbols or practices should not be prohibited or criminally sanctioned. In another report to the General Assembly, the Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression reiterated the Human Rights Committee's jurisprudence that this right does embrace expressions that may be regarded as deeply offensive, such as blasphemy.” (Collective exercise for 20 -30 minutes).

Storytelling: Participants comment on situations that have happened to them personally or that they witnessed pertaining to this commitment and how they handled them. “Blasphemy” and “apostasy” are not only legal notions but may occur in daily life. In particular, has there been a situation where participants had to intervene in defence of a person who had been accused of blasphemy or apostasy? What type of social reactions are more likely to occur in the participants’ surroundings when there are public instances of blasphemy or apostasy? Provide examples of the positive or negative role played by the media in this respect. (Collective exercise for 15 minutes).

The facilitator could also refer to the following quote from Andrew Copson, President of Humanists International, who stressed that anti-apostasy and anti-blasphemy laws “remain one of the most egregious forms of legal discrimination against the non-religious, as well as other religion or belief minorities, in that they are used most often against members of religion or belief groups outside the mainstream of a country.

The ‘blasphemy’ cases that most often hit the headlines include artists and writers, protesters and activists, who through their creative or social work cause ‘offence’ to a mainstream religion. Sometimes the offence as such is somewhat intentional, as when a novelist plays with the bounds of faith, or an artist depicts some aspect of faith or criticism in a novel, or satirical mode. Other times, ‘blasphemy’ laws and taboos are used to intimidate or prosecute people who express dissent against some aspect of mainstream religion, whether from ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the tradition. This can mean that criticism of particular beliefs, practices, leaders or institutions is made taboo, even when there is a clear moral case for debate, criticism, reform or justice.”

Tweeting: Summarize the commitment XI within 140 characters (individual exercise for five minutes).

One possible result of this tweeting exercise could be as follows: “We commit not to oppress critical voices on religious matters in the name of ‘sanctity’, and to advocate for repealing any anti-blasphemy and anti-apostasy laws”.

Translating: Similar to the tweeting exercise, participants could be asked to “translate” this commitment into child-friendly language or into a local dialect. Again the idea is to stimulate discussion about the most important elements and appropriate ways of transposing and simplifying the message, without losing the substance of the commitment.

Simulating: Simulation of an adversarial debate leading to an arbitration on a case related to anti-blasphemy and anti-apostasy laws. This collective exercise would require a length of time ranging from an hour up to a full day. This depends on the complexity of the case to debate as designed by the facilitators. Participants could be divided into three groups to simulate a moot court with applicants, respondents and judges.

Simulating: Simulation of an adversarial debate leading to an arbitration on a case related to anti-blasphemy and anti-apostasy laws. This collective exercise would require a length of time ranging from an hour up to a full day. This depends on the complexity of the case to debate as designed by the facilitators. Participants could be divided into three groups to simulate a moot court with applicants, respondents and judges.

Adding faith quotes: Participants strengthen the faith roots of commitment XI by suggesting additional religious or belief quotes on the subject matter (individual exercise for five minutes, followed by a reading from each participant of his added reference).

Inspiring: Participants underline artistic expressions they know of which capture aspects of commitment XI. Using artistic tools by faith actors could facilitate an important shift towards a constructive role of faith actors with respect to peace, development and human rights in their own local spheres; it is at that level that sustainable change should begin. One of the main sources of inspiration for facilitators in this respect can be found in the history of religious reforms and related artistic expressions.

Facilitators could also refer to the novel “Children of Gebelawi” by Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz as an interesting example to illustrate that societies may ban a book for years before realizing that ideas cannot be banned. The controversy here centred on the question whether the main character of the novel, Gebelawi, is a figure of God or only a symbol of religion. In parallel with Gebelawi’s mysterious character, the novel tells the stories of selected figures from society favoured by Gebelawi himself. For some conservatives these characters represented prophets; for others they were merely symbols of the religious values adopted by individuals and how they improved life around them by ensuring respect for these human values. This example shows that literature, like any other form of expression, can be understood in whichever way the recipient interprets it. Expression should be free, as long as it does not incite violence or discrimination or constitute a specific crime under laws that are compatible with international human rights obligations.

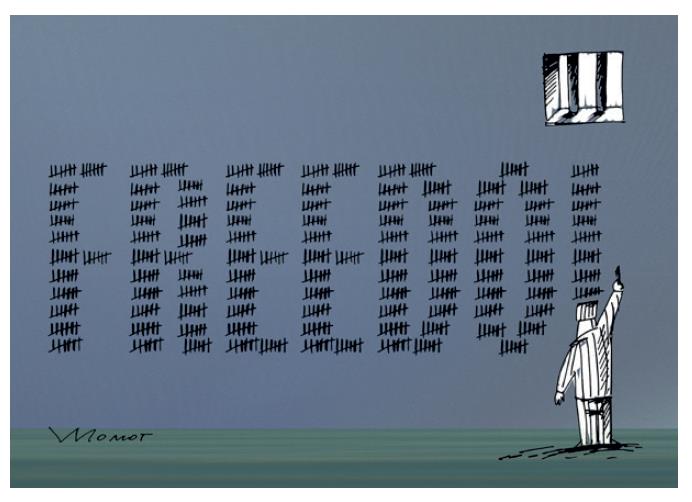

In addition, please find here the example of a cartoon and calligraphy. In May 2021, Freemuse and OHCHR also organized a webinar (video) on “Speaking Truth to Power: Religious or Belief Minority Artists, Voice and Protest”, discussing cases where artists have been threatened by anti-blasphemy laws and other forces limiting civic space.

In addition, please find here the example of a cartoon and calligraphy. In May 2021, Freemuse and OHCHR also organized a webinar (video) on “Speaking Truth to Power: Religious or Belief Minority Artists, Voice and Protest”, discussing cases where artists have been threatened by anti-blasphemy laws and other forces limiting civic space.

Learning objectives

- Participants appreciate their responsibility to promote – not just tolerate – critical thinking on religious matters. They understand that diversity enriches religious thinking and strengthens societies in facing new challenges.

- Participants realize that new communication technologies naturally lend themselves to free exchanges. They understand the utility of acquiring inter-faith and inter-cultural competencies to manage the diversity of views in increasingly pluralistic societies with a free flow of views and information, both true and fake.

- Participants realize that new challenges facing our societies should encourage us to be better listeners and enrich our judgements with nuance. Not all questions have a “yes-or-no” answer, nor should they.

previous module ¦ overview ¦ next module >