Module 10: Instrumentalization

#Faith4Rights toolkit

Full text of commitment X:

| We pledge not to give credence to exclusionary interpretations claiming religious groundsin a manner that would instrumentalize religions, beliefs or their followers to incite hatred and violence, for example for electoral purposes or political gains. |

Context

Since their earliest beginnings in human history, religious and political powers have competed for influence. It took centuries of tensions and wars to define their boundaries and modes of interaction. Yet, multi-faceted ambiguities and overlap between religion and politics persist. The modern-day separation of the state and religious authorities does not equally apply across the globe. The overarching question that this module addresses is how to avoid the manipulation of religion in public discourse for political gain or electoral purposes, in a manner that leads to exclusion, discrimination, incitement to violence or any other human rights violations.

Additional supporting documents

In support of the peer-to-peer learning module on commitment X, the training file could include the text of the statement by High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet at the Global Summit on Religion, Peace and Security(April 2019): “Human rights are closely connected to religion, security and peace. Religious leaders play a crucial role in either defending human rights, peace and security – or, unfortunately, in undermining them.

In support of the peer-to-peer learning module on commitment X, the training file could include the text of the statement by High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet at the Global Summit on Religion, Peace and Security(April 2019): “Human rights are closely connected to religion, security and peace. Religious leaders play a crucial role in either defending human rights, peace and security – or, unfortunately, in undermining them.

Supporting the positive contributions of faith-based actors is crucial, as is preventing the exploitation of religious faith as a tool in conflicts, or as interpreted to deny people’s rights. Human rights and faith can be mutually supportive. Indeed, many people of faith have worked at the heart of the human rights movement, precisely because of their deep attachment to respect for human dignity, human equality, and justice. I am convinced that faith-based actors can promote trust and respect between communities. And I am committed to assisting governments, religious authorities and civil society actors to work jointly to uphold human dignity and equality for all. In recent years, my Office has been working with faith-based actors to conceive the ‘Faith for Rights’ framework. Its 18 commitments reach out to people of different religions and beliefs in all regions of the world, to promote a common, action-oriented platform. The ‘Faith for Rights’ framework includes a commitment not to tolerate exclusionary interpretations, which instrumentalize religions, beliefs or their followers for electoral purposes or political gains. In this context, it is vital to protect religious minorities, refugees and migrants, particularly where they have been targeted by incitement to hatred and violence.”

Peer-to-peer learning exercises

Unpacking: Participants break down commitment X into different elements. Facilitators will bear in mind that this commitment is among the most complex ones as it touches upon the question of “religions in politics” and the “politics of religions”. Defining manipulation and instrumentalization, while respecting freedom of expression is not an easy task– especially when manipulators are smart, which is usually the case. This means that both facilitators and participants have a higher potential to flesh out and even reshape this commitment in many different directions in light of their own experiences. Commitment X is also heavily contextual. Facilitators therefore have a large room to animate, through this commitment, a discussion that is targeted and tailored to national and local realities. Once again, not all issues can be resolved. However, identifying the subtleties of certain issues, like the one under consideration, creates needed awareness and stimulates cautious reflection by faith actors as to how to pre-empt the expected manipulation of their faith and moral weight for political purposes. (Individual exercise for five minutes followed by ten minutes of a full group discussion on the differences between individual listings).

Unpacking: Participants break down commitment X into different elements. Facilitators will bear in mind that this commitment is among the most complex ones as it touches upon the question of “religions in politics” and the “politics of religions”. Defining manipulation and instrumentalization, while respecting freedom of expression is not an easy task– especially when manipulators are smart, which is usually the case. This means that both facilitators and participants have a higher potential to flesh out and even reshape this commitment in many different directions in light of their own experiences. Commitment X is also heavily contextual. Facilitators therefore have a large room to animate, through this commitment, a discussion that is targeted and tailored to national and local realities. Once again, not all issues can be resolved. However, identifying the subtleties of certain issues, like the one under consideration, creates needed awareness and stimulates cautious reflection by faith actors as to how to pre-empt the expected manipulation of their faith and moral weight for political purposes. (Individual exercise for five minutes followed by ten minutes of a full group discussion on the differences between individual listings).

Linking the dots: Discussing the relationships between the components of commitment X could require facilitators to join various dots. These may include: religions in conflict; religious wars in history and their possible residual impact; and the importance of objective research to establish historical facts whose distortion may fuel contemporary conflicts. Again, such problems need to be highlighted but their resolution is not the aim of the discussion. This collective exercise may take more time than the facilitators have planned for, so they should manage the time well by trying to reach a better understanding of the components rather than to agree on conclusions that are unlikely to be reached. The target is to normalize discussion of such taboo matters.

Critical thinking: A critical discussion on the relationship between these elements can stimulate eye-opening discussions. How do participants experience and navigate the “mine field” of religion and politics in their respective environments? Where to draw the line between their needed social involvement as engaged faith actors and the poisonous political manipulation of religious actors? What criteria do participants suggest in this respect, knowing that this objective difficulty explains why commitment X is rather brief and does not even try to define “instrumentalizing religions, beliefs or their followers”, leaving it to a case-by-case assessment made by practitioners themselves? Are there any other examples other than “for electoral purposes or political gain”? Do participants think that there are missing elements in commitment X? How can their mere awareness of this risk help faith actors to reduce its chances of recurrence? (Collective exercise for 20-30 minutes)

Storytelling: Participants are invited to share situations that they have experienced pertaining to this commitment and the way they handled them. In particular, was there a situation where participants were involved in public political debates or had to intervene in a political context? Participants can also share examples from their respective environments of the positive or negative role played by the media in this respect? (Collective exercise for 15-30 minutes.)

In the context of political instrumentalization, the facilitator could also refer to the following example raised by Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed in his 2019 report: “Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an ethnic Chinese Christian, serving as the Governor of Jakarta, was a candidate in the gubernatorial elections scheduled for 2017.

He referred to a Qur’anic verse in a speech he made during his gubernatorial election campaign. Some groups objected to the reference, as posted online in a video, which seemed to have been edited to omit a word, which led to a misinterpretation of his speech. Some organizations reported Purnama to the police and accused him of having committed blasphemy. Purnama publicly apologized and clarified that it had not been his intention to offend. Nonetheless, a fatwa was subsequently issued and during large-scale protests, rally leaders reportedly made statements which incited hatred and intolerance. These protests were claimed to be politically motivated to defeat Purnama in the gubernatorial election. Although Purnama’s defence team presented evidence of various procedural errors in the police investigation, the court denied their motion to dismiss the case. On 9 May 2017, Purnama was found guilty of blasphemy and of inciting violence by the North Jakarta District Court, and he was sentenced to two years in prison. On 24 January 2019, he was released three and a half months early under the remission laws of Indonesia, which grant prisoners leniency on public holidays and for good behaviour.”

See also the panel discussion during the International Conference on Islam and Human Rights, held in Jakarta on 10 December 2021, as well as the Gerakan Pemuda Ansor Declaration on Humanitarian Islam, adopted at the international gathering of Ulama in Jombang on 21-22 May 2017.

Tweeting: Summarize the commitment X within 140 characters (individual exercise for five minutes).

One possible result of this tweeting exercise could be as follows: “We commit not to tolerate exclusionary interpretations on religious grounds which instrumentalize religions, beliefs or their followers for electoral purposes or political gain”.

Translating: Similar to the tweeting exercise, participants could be asked to “translate” this commitment into child-friendly language or into a local dialect. Again the idea is to stimulate discussion about the most important elements and appropriate ways of transposing and simplifying the message, without losing the substance of the commitment.

Exploring: The type of questions suited for commitment X for the use of facilitators may include: Why is instrumentalization of religions wrong? Why did this phenomenon start very early in the history of religions? Can it be redressed? How? Is there a normative gap in this area? Or is it more about policies rather than laws? What should be the reaction of a religious leader when religions, beliefs or their followers are instrumentalized for electoral purposes or political gains? (General discussion for 15 minutes)

Adding faith quotes: Participants suggest additional faith-based quotes in support of commitment X (individual exercise for five minutes, followed by a reading from each participant of his added reference).

Adding faith quotes: Participants suggest additional faith-based quotes in support of commitment X (individual exercise for five minutes, followed by a reading from each participant of his added reference).

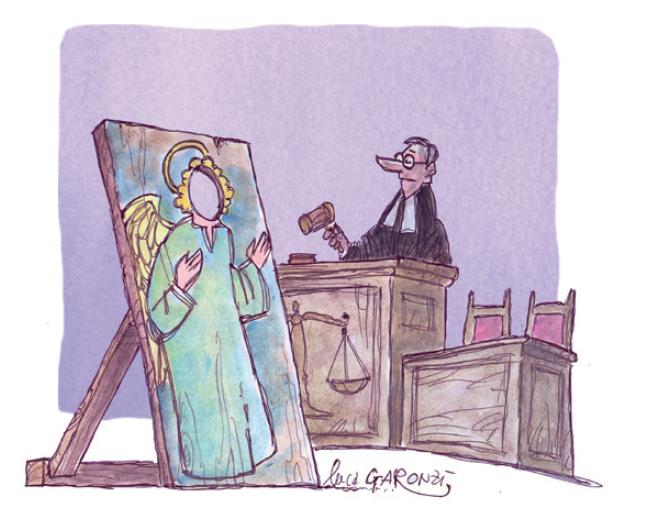

Inspiring: Participants may share artistic expressions that they know of and which capture aspects of the commitment under discussion.

In addition, please find here the example of a cartoon and calligraphy as well as music.

Learning objectives

- Participants appreciate their responsibilities towards diversity and pluralism in their respective societies.

- Participants realize the importance of their intellectual integrity and autonomy from political parties and actors. They become aware of the possibility of being manipulated in political quarrels and the risk of polarization and discrimination to which this could lead.

- Participants remain socially engaged and entitled to their views in public debates. However, they become more clear-minded and self-restrained in drawing a distinction between their public responsibilities as faith leaders and their personal views as individual citizen.

previous module ¦ overview ¦ next module >