Child migrants’ future in Italy “must not depend on luck”

09 August 2016

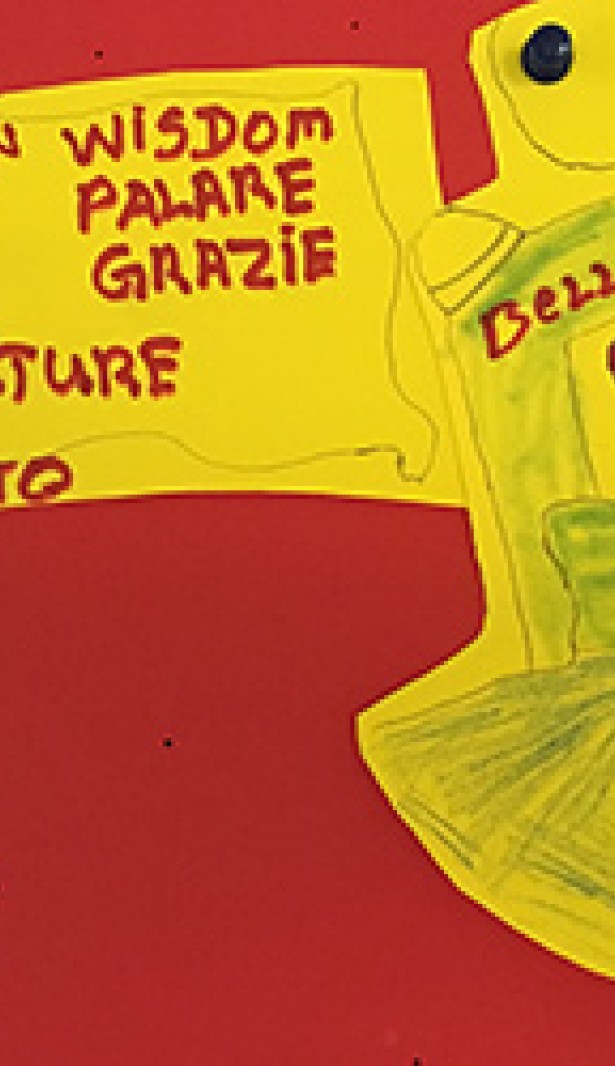

The House of Cultures in the small Baroque town of Scicli in south-eastern Sicily is full of colour, from the huge dramatic murals to the green, orange, blue and purple timetables in different languages to the photos of beaming teenagers under the legend inostri campioni di calcio – our football champions.

The centre, run by Mediterranean Hope, a project of the Federation of Protestant Churches in Italy, was looking after some 24 unaccompanied and separated child migrants when a team from the UN Human Rights Office visited in late June.

“Our house is meant to be a safe place for the most vulnerable migrants, but it is also meant for temporary stays of up to three months. Our priority is to find good and more permanent places for the children to live, or reunite them if they have family in Europe, and that is a challenge,” said Giovanna Scifo, who manages the centre.

Italy has very good legislation regarding children, said Imma Guerras-Delgado, Child Rights Advisor at the UN Human Rights Office. A migrant who is under-age is given residency and has the same rights as Italian children.

But the country faces an ongoing challenge amid the rising numbers of unaccompanied child migrants, the overwhelming majority of whom are boys aged 15 to 17 years. In 2015, some 12,000 unaccompanied minors entered Italy. So far this year, some 15,000 unaccompanied children have arrived, accounting for 15% of the total number of migrants reaching Italy’s shores, according to UN Refugee Agency figures.

The Italian Government says it has increased its financial support for the care of unaccompanied children, from 90m euros in 2015 to 170m euros in 2016. But the chronic lack of appropriate places to house the children means they can remain for weeks and even months in facilities that are designed for short stays, with little or no provision of education, counselling or child-friendly activities.

“I visited an excellent government-run centre in Palermo that currently houses some 15 girls, some of them very young, just 12 or 13-years old,” said Guerras-Delgado. “But we are concerned that some centres for children are overcrowded and not properly monitored. We heard repeated complaints from the children that they have never seen a lawyer to help them with their legal processes, are completely in the dark about their future, and, at some centres, have nothing to do.”

Different centres seem to have different standards, and this needs to be harmonised, Guerras-Delgado stressed. “The rights of the child, of all children, cannot depend on luck. Rights are entitlements and cannot simply be a matter of luck. If you’re lucky, you get the best centre; if you’re not so lucky, you go to another centre with all the implications that may have for your future,” she said.

The future seemed unclear for a 16-year-old boy, who told the UN team he had been in the “hotspot” centre on the island of Lampedusa for more than a month.

“I spent two months in prison in Libya, I was beaten, I was forced to work to pay for the boat,” the boy said, his voice rarely rising above a whisper as he described what happened to him along the smuggling route from West Africa. “Everything is OK here but I don’t know when I can leave,” he said.

Had he received information about what would happen to him? “I forgot,” he said, the exhaustion of telling his story clear on his face.

For Guerras-Delgado, the tremendous potential of the children she met at the reception centres is one of her abiding impressions.

“They can contribute to Italian society at every level. That’s why it is so important to make sure that rights do not depend on a child’s luck in being assigned to a centre,” she said.

Giovanna Scifo and her colleagues at the House of Cultures echoed this, stressing the importance of providing the right care, including psychological support, to children who have left their country and their familes and often suffer depression and nightmares due to the trauma they have experienced. To help the child migrants integrate, the House of Cultures provides the opportunity to learn Italian and the children attend local schools.

Right on cue, several boys emerge from their daily Italian class at the House of Cultures, ready to practise what they have learned.

The UN team says hello and the boys pause for a couple of seconds.

“Buon appetito!” they reply with big smiles.

This is the final article in a four-part series about the mission to Italy by UN Human Rights Office team from 27 June to 1 July. Read the others here:

- Security at forefront as Italian island receives migrants

- Migrants cling to their dreams as they await uncertain future

- Italy’s migrant hotspots raise legal questions

9 August 2016